I believe one of the most damaging pieces of advice to proliferate in the tech world over the past few years has been “being early is indistinguishable from being wrong”.

There are many reasons why this is true in theory but as I’ve talked about for years, at this stage of technology development and penetration, whether you’re a technologist or capital allocator, if you’re not too early, you’re too late.

As venture markets continue to institutionalize, this becomes more true with consensus startups getting rampantly bid up in price. This leads to a compressing of returns and forces growth-stage investors to have asymmetrically upside-skewed beliefs on terminal outcomes in order to capture meaningful alpha.

Concurrently, technology as an asset class has continued to evolve and is now going through a next major wave that could lead to market cap dislocation at a far faster pace and grander scale than this past decade.

Put simply, if the prior decade of technology as an asset class was about incumbent industries being swallowed up by tech, leading to an expansion of the market cap of “tech” as a category, than the next may be about disruption and market cap destruction within tech itself.

What this means is that there will be parallels of businesses that are “tech” versus “non-tech” versions as well as “new tech” versus “old tech” versions. With this dynamic comes a necessity to create legibility in order to properly (or improperly) analyze and value these new types of technology businesses. People do this by changing the terminology and descriptors surrounding these companies, a cycle that continues to happen over and over again.

How Capital Flows Through Assets

At a high level, category creation occurs as an exercise to draw in capital, create legibility, and then create novel re-rating or “multiple expansion” of an opportunity.

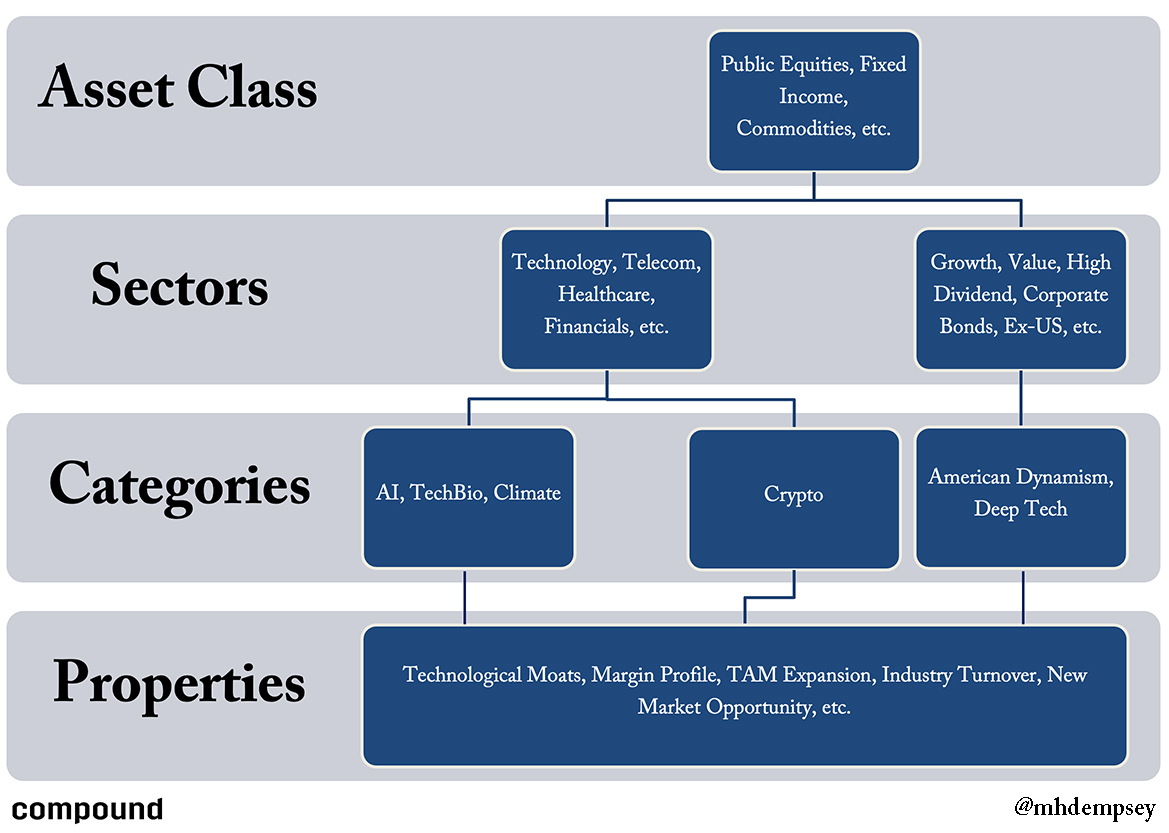

The chart below details this entire dynamic.

Capital needs structure in order to properly flow through the system.

We look at this at an Asset Class level. An asset class has a few high level properties like timeline, risk, and business dynamics that allow large sums of money to be bucketed. The examples in my chart above are Equities, Fixed Income, Commodities, and many others.

Let’s now follow the equity-like instrument component down the rabbit hole further to get a better grasp of how we get from there to a novel category.1Yes, I know this chart doesn’t only look at equities

Assets then progress into Sectors that are based on the area of focus (Technology, Telecom, Healthcare, Financials) or higher level properties of the asset from a risk or metrics perspective (Growth, Value, ex-US).

Sectors enable people to then begin to allocate a relatively finite amount of capital across entities in a zero-sum way (people will make explicit decisions of wanting to be in equities, and then within that deploy into sectors like technology or telecom or growth, etc.).

As Sectors become more well-understood, market participants look for ways to further differentiate a basket of companies or investible assets in order to capture flows, or theoretically to increase the flow into the broader Sector. This is where Categories are created and perhaps is the key thing to understand about why capital creation happens.

Novel categories are created in order to differentiate a sea of companies with market-wide illegible properties, in an effort to create multiple expansion or a re-rating dynamic within the given sector.

Put more simply, people name things something novel so that they can tell other people that Company A in Category X is a better company than similar incumbent Company B in Category Y. Alternatively, they give a name to Category X because the technology itself or the companies within them were too difficult to understand or not marketable enough.

Not machine learning, but AI. Not digital worlds but The Metaverse. Not Blockchain but Crypto…well actually, Web3.

These categories are built around narratives that people hope will come true across a variety of fundamental property types. These properties can include but are not limited to:

- Technological Moats: This tech is so hard it deserves a higher multiple

- Margin Profile: This business is better than other similar businesses because of a business model or tech-enabled shift

- TAM Expansion: This market is going to get much bigger, leading to inflections in revenue/moats/scale

- Industry Turnover: Incumbents are going to secede market cap at a rate that is under-appreciated, so the business deserves a higher multiple based off of future revenue growth/ scale that is under-appreciated

- New Markets: This market didn’t exist and will be big, thus you need to have money allocated to it

- And many many others.

Across all of these narratives the idea is that you can create new forms of distilled legibility around previously broadly illegible companies and then create multiple expansion either from increased capital flows and/or a belief in company superiority. You do this with the hopes that this expansion lasts for a long enough period of time that these companies prove their narratives.2In many cases, this was done with SPACs and these companies had far too little proof points to command their narrative premiums, which collapsed as markets grew impatient with missed projections and interest rates shifted

This can look like SpaceX changing the economic operating model of space companies due to technical moats, operational shifts to change margins, and industry turnover/TAM expansion.

It can look like automation disrupting the margin profile of a large number of OpEx heavy or labor heavy companies as broader macroeconomic shifts erode their operating models.3This is perhaps a good example of the next decade of tech disruption vs. enablement dynamic I mention earlier in this piece

It can look like AI rapidly expanding the TAM for a variety of types of software as Adobe recently talked about in their earnings call as it related to new users and their subscription growth around Cyber Monday.4Obviously AI can do a lot of things to shift businesses, let’s not make this an “AI CHANGES EVERYTHING” post.

It can be the use of multiple technologies, like better software, robotics, and AI which could shorten the time at which drugs get to market or the efficacy of which we can get drugs to market.5I know people doubt this, don’t Eroom’s law me.

And of course this could look like Anduril or a variety of other American Dynamism type companies that are not just government contractors or private equity style businesses with a premium applied by VCs, but are instead technological powerhouses with a better, higher leverage economic and business model.

It is to be seen whether any of these narratives actually ring true before investors begin to lose faith in them, as they have for periods of time in deep learning, crypto, virtual reality, clean tech, and a bunch of other areas that captured large premiums once they were deemed a category or a theme.

All in all, we’ve seen this narrative proliferation happen multiple times, perhaps most consistently in the form of SPACs that used a playbook over pairing a category with a single company and upon going public, the company would be framed as “The only pure play ___”.

Weak narratives should be appreciated as they are likely a signal for a market top or a company that doesn’t have any other more meaningful proof points, which as we saw with SPACs, led to a bunch of pure play companies that lost 90%+ of their equity value, signaling a local top in the category and/or market.6Crypto also has this in late cycle or bear markets with things like Privacy entering the mainstream or far-fledged consumer visions like the metaverse in 2021.

Thematic ETFs as a Proxy

Over and over again we grasp for this form of legibility either out of laziness, an inability to parse novel businesses, or perhaps more nuanced reasons like lack of resources on the equity research side of things or a belief that we’re fucked unless we take massive risk. This happens across both public and private markets.

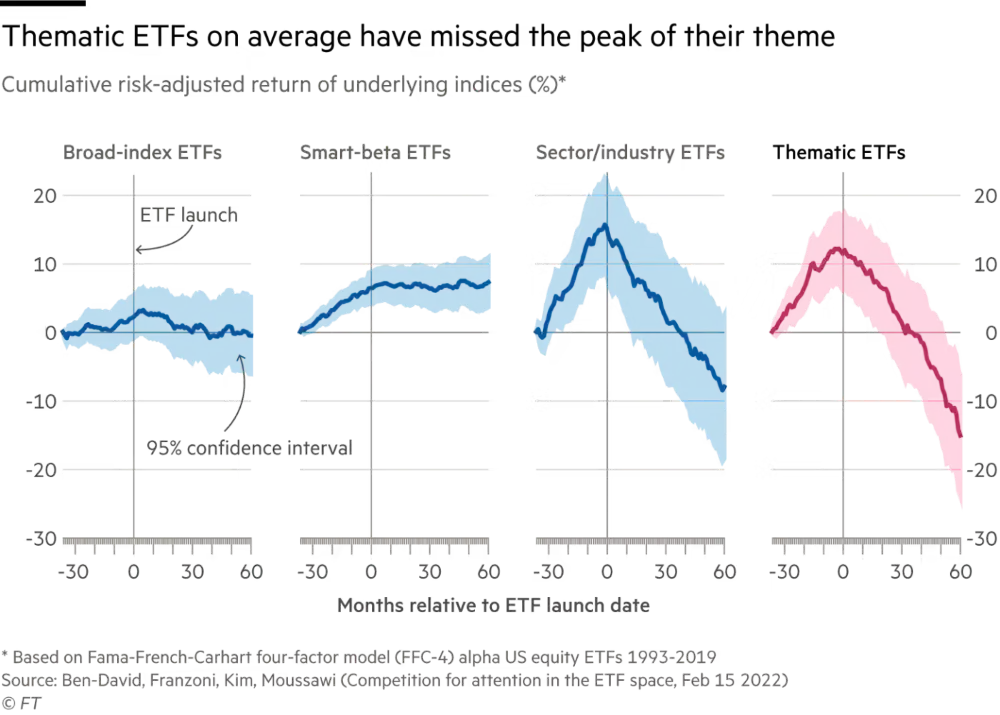

Despite my constant screaming into the internet that markets the past few years have been more narrative driven than all prior periods (and that we were going to dial back a bit), you can see the data in the inflows for thematic ETFs as a proxy with a massive increase in flows (and a slight pull back in the past 24 months). Specifically, we’ve seen technology capture the lion’s share of thematic ETF capital as well.

If we use that as a proxy for value capture of returns, what we then see is that by the time something is a “theme” and an ETF is launched, returns have topped.

Connor Mac summarizes this data and points well with his post Here is the Problem with Thematic ETFs in which he says:

“There are inherent ironies in a thematic ETF. To capture the benefits of a rising trend, you need to get in at the ground floor; i.e., be early. By the time someone has constructed a financial instrument to express that theme, it’s likely already had its 15 minutes of fame. While the upside can be explosive when it works, the odds are usually stacked against the investor in a thematic ETF.”

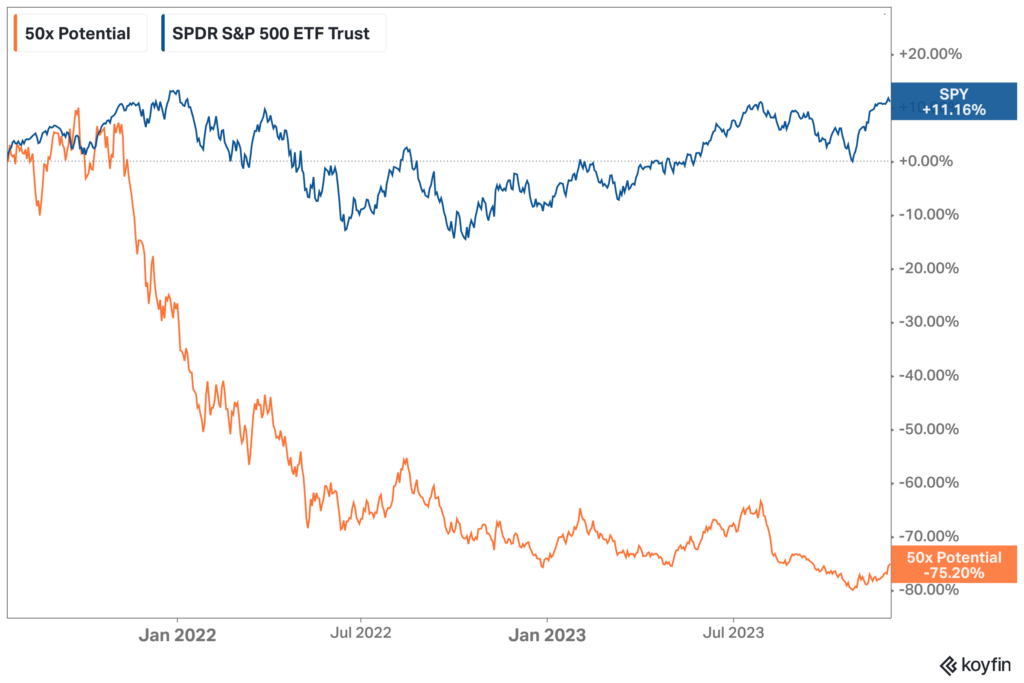

He took this analysis a step further in another post called GroupStink which looked at the most popular responses to “What company is worth less than $10 billion today but you think could be worth $500+ billion in a few decades?” and analyzed them relative to the S&P 500. The performance speaks for itself and further highlights why crowding into ideas or narratives likely signals an erosion of relative (and in this case absolute) performance.

Category Creation and Venture in 2024

Throughout 2023 it became clear to me that venture capital as an industry had lost a lot of confidence in itself.7This was a net positive as we all had a bit too much confidence over the past few years This creates some interesting behaviors for an investor group that is largely reactive to markets and likes to repeat the canonical wisdom that founders should show us the future and it’s our job to only see the present clearly.

However, when there is no present that can be easily and clearly seen, people begin to look to others, embrace groupthink, and cycle through conviction.

In a way, category creation is as much about finance as it is about psychology and sociology – it taps into investors’ desires to be part of something novel and potentially revolutionary. Founders would be well-suited to understand this dynamic and position their company properly as they look to raise capital and compete against other well-funded players.

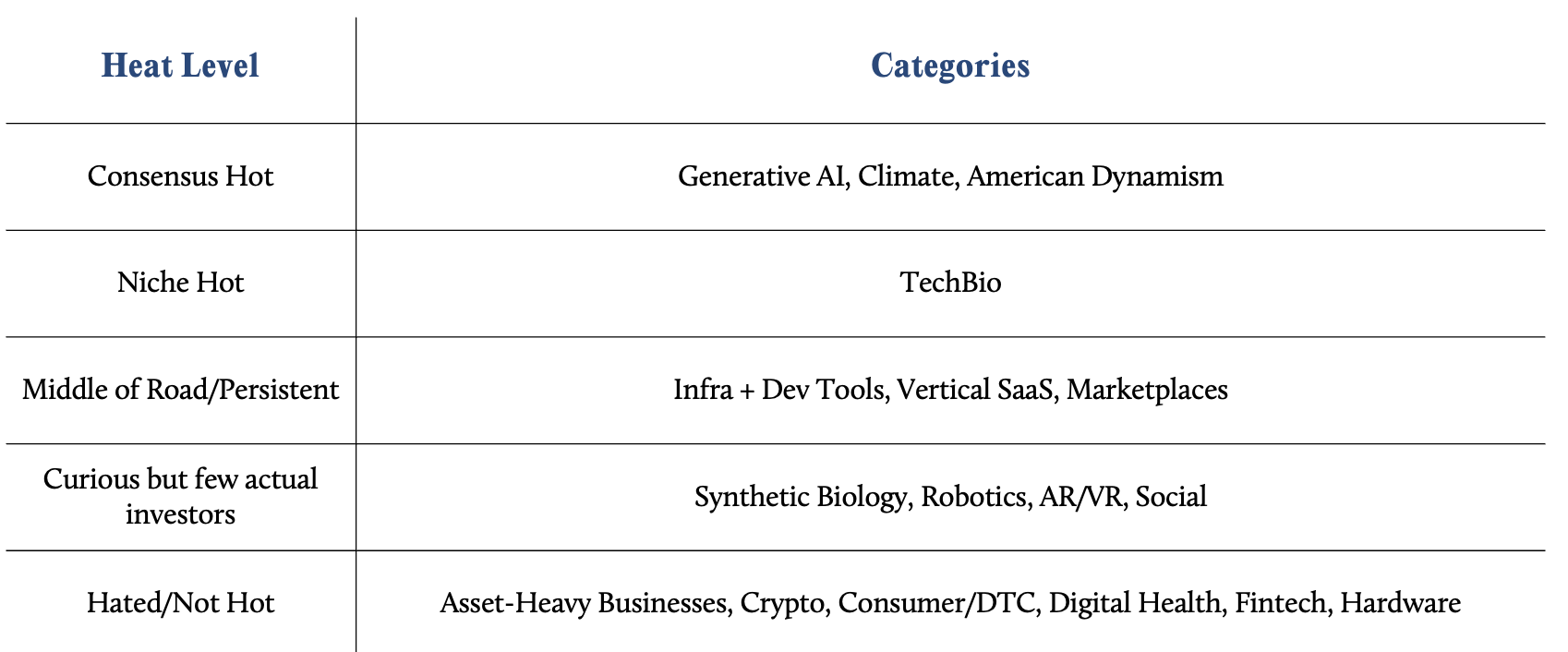

With this said, if we look at a few of the underlying categories with the most “heat” according to a single person8Me, so take it with a grain of salt, we quickly learn that the legibility is quite poor relative to the underlying business models or other nuanced dynamics that makes these companies unique/special.

Put another way, categories like Generative AI, American Dynamism, Climate, and TechBio (all areas we as a firm have invested in and believe in) don’t actually mean anything or add any additional clarity to the futures these companies create or help parse how value may accrue within a given technological breakthrough.

As confidence has been lost we’ve seen a bifurcation of investors who are either retreating to categories they believe they know very well and/or are scope creeping into novel deep tech categories that they have never previously spent time in but they hear could be the next thing.9We also see founders pivot around from time to time how they position themselves or even how they prioritize roadmap and hiring in order to capture narrative value.

A potential hypothesis for the latter is that, like the past few years of ZIRP, deep tech at times enables VCs to get premiums or multiple expansion based off of a fuzzy understanding of the world (AI will be big is the new Software is Eating The World) versus the clearer understanding of areas that have had stronger multiple compression (Fintech, SaaS, Marketplaces) with well-understood business models across multiple types of market participants.

Perhaps investing in well-understood businesses is hard mode while yeeting into companies with strong narratives but poor fundamental clarity is easy mode in the mark-ups driven game of venture capital.

Of course, like the early understanding of revenue quality and TAM in SaaS was a meaningful alpha generating opportunity for a period of time, there will likely be other categories that make many investors a lot of money. That said, due to the scale of venture capital and technology in 2024, the windows will be far smaller and the penetration of investors flocking to it will be stronger, creating faster feedback loops and tighter bubble windows.

This, like all dynamics in startups and venture, will end in the same place; with a massive divergence of returns (and compression of alpha). This was shown recently by Citrini Research in the tweet above which analyzed public market returns of AI companies and how quickly that alpha eroded in the short-term.

Technologies as Substrates

There are a lot of concepts that circle around this idea of category creation, however it is most likely that each type of participant can learn something differently by watching it unfold in their respective area of technology. Investors can use these concepts to identify tops and direct their behavior and focus, while founders can use them to play the game of capital raising and brand building uniquely well.

The natural way in which one would wrap up this piece is to walk through the practice of getting to categories early and how one could analyze them, while also talking through how founders can build idea moats early on. Instead of doing that10Typically this is reserved for friends, portfolio founders, or LPs…and also this is probably best suited for another post someday I will leave you with a push to re-think why we care about technology.

The art of category creation is important over the short to mid-term in order to understand how capital flows through a system and to take advantage of that to impact the future. It is because of this, that instead the real importance of building a process is to recognize that technologies (and capital) are not the thing but instead are merely the substrates that enable us to get to the various futures that we believe in.

Recent Comments