At Compound, we spend a lot of time thinking about the transition periods between core Research/Science and Company Building and have oriented our firm to help founders building at this intersection. Over the past few years, we’ve noticed a structural shift in this period of technological development that is now reverberating throughout both research communities and the startup ecosystem.

In recent history, groups of people in deeply technical or scientific areas would implicitly (or explicitly) separate themselves as Research Groups, Applied Research Organizations, and Companies.

The left end of the spectrum was for those only interested in solving technical problems and the right was for those commercializing and productizing technology that was largely ready at scale.

The Applied Research Organization, which takes early novel research and expands upon it with the goal of creating a closed-loop value capture organization (company) has now become the far more natural state of this paradigm in startups.

This is great for progress, good for capitalism, and likely unnatural for a variety of given spaces that are earlier in their cycles than traditional AI is, for example.

Playing Venture Games

The top talent now understands their market signal and use it to capture large sums of capital to go after a broader “area” with a looser idea of product/GTM than many boomer investors expect. They observe the supply/demand imbalance of top talent, and thus raise enough money up front to rip out a large chunk of their current team/lab or a collection of labs under the (correct) thesis that a focused startup can make more progress than a constrained R&D group in a large company or institution.

The earlier generations of this looked like a top professor being pulled by a few great students, then progressed to larger groups led by top executives, like Nuro/Aurora or Anthropic, each splitting off with very large fundraises and collections of talent aimed at doing what the incumbent was doing but better or slightly adjacent (in Nuro’s case).In AI, it’s even more clear this pillaging of academia will continue to happen as maybe for the first time in history, the dollars in large not-for-profit institutions aren’t properly allocated to empower the research/science. Put simply, universities and research orgs aren’t buying enough GPUs to push forward experiments that require scale of any kind.

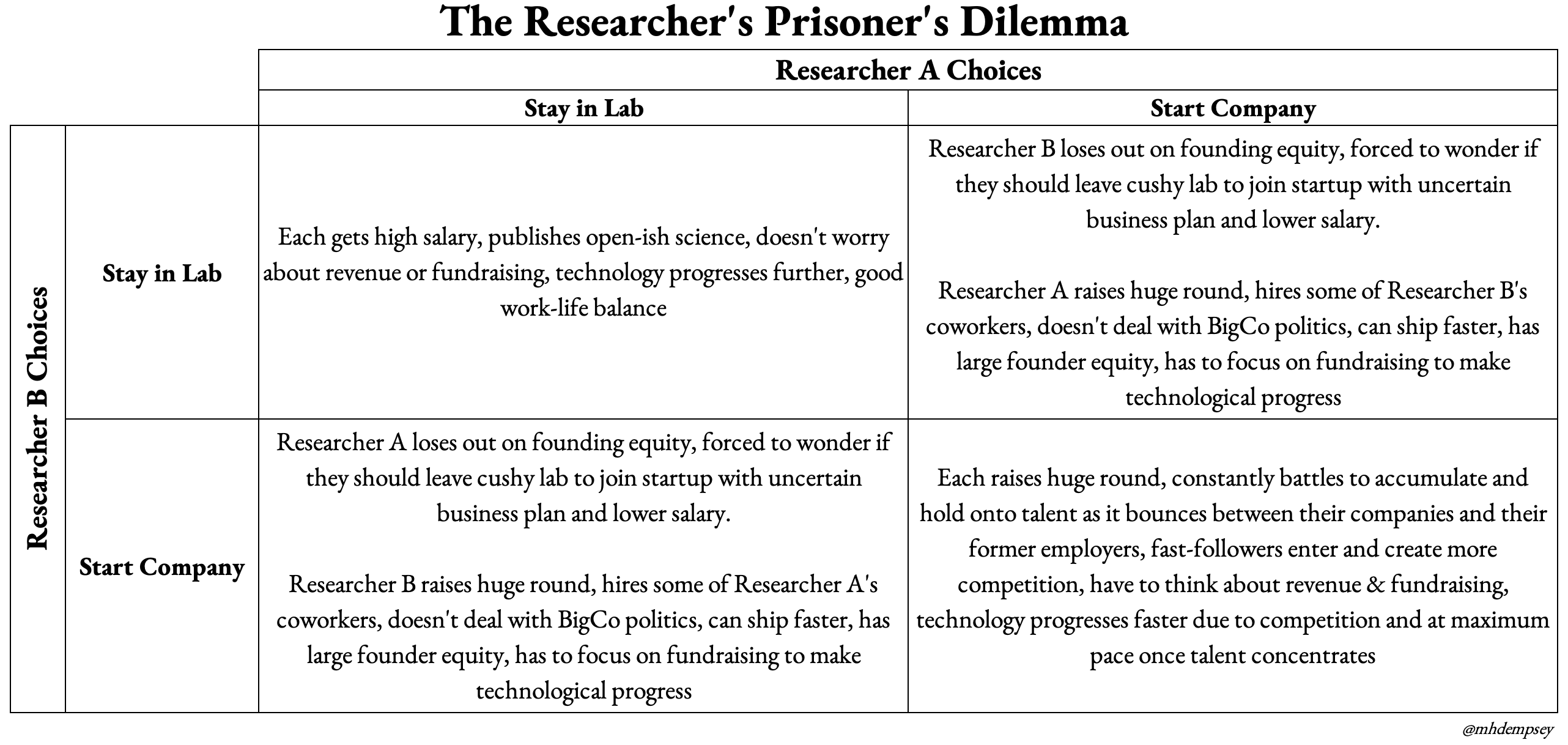

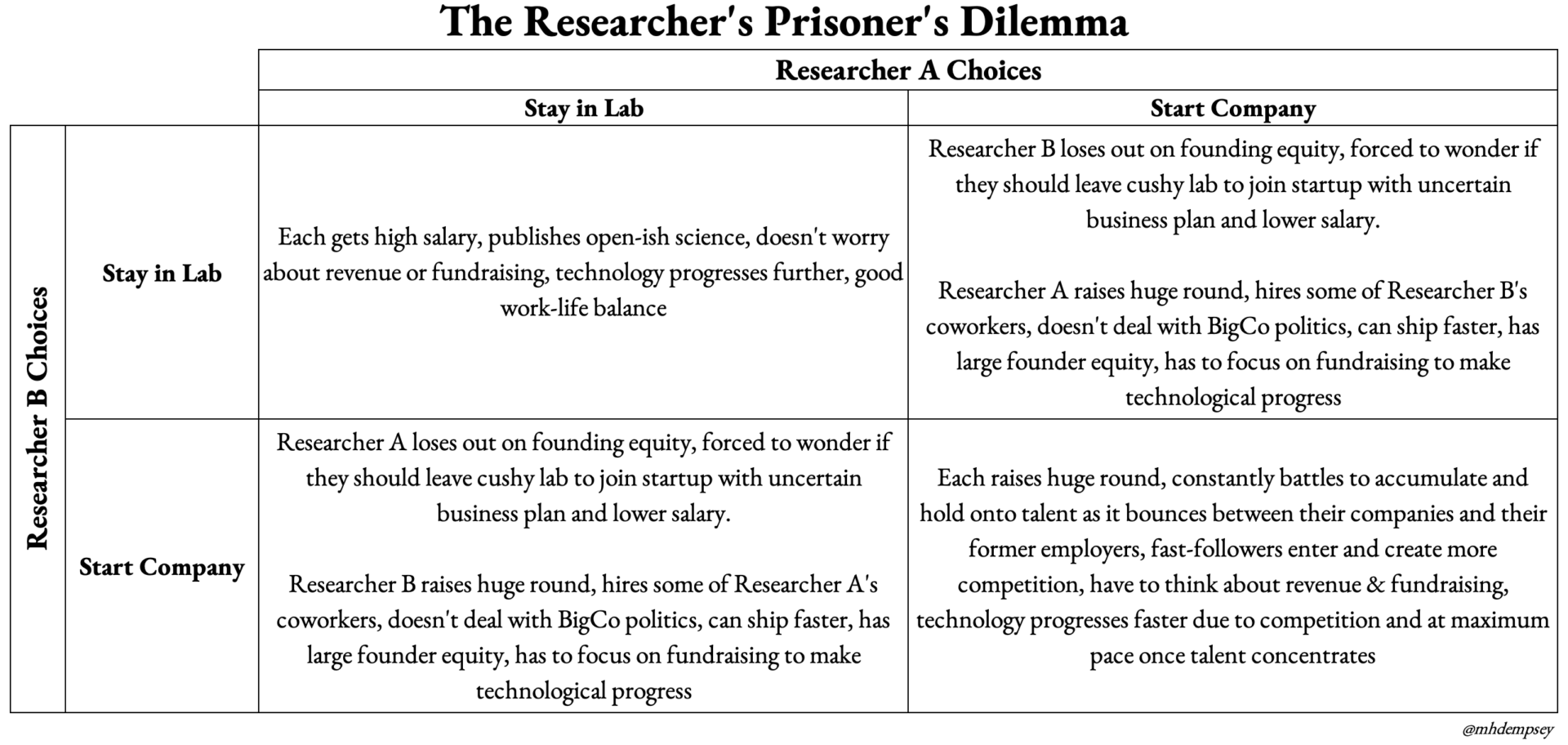

In my prior post I talked about the progression of R&D groups into Startups, but didn’t expand on competitive dynamics outside of Robotics and more broadly a theory I call the Researcher’s Prisoner’s Dilemma.

In 2024, with so many dollars at stake and so many investors circling, it increasingly feels as though the top researchers in a given space are playing a game of Chicken where everyone is looking to see who raises money first and then once one person does, everybody does. With each researcher’s decision comes material trade-offs.

A Prisoner’s Dilemma.

This is great for large funds (and maybe all VCs) because they can write a lot of call options and capture the value of research in a more purely capitalistic way, betting that the venture-backed research either will create value via acquisition (something that we see at beginnings of technological paradigms as shown with companies like Deepmind, Geometric Intelligence, Otto, CTRL Labs, etc.) OR will create value as a team that can bridge to productization and distribution of the research.

The former path requires a healthy regulatory environment and an unwillingness of founders to abandon their companies in the new AI-style acquisition pioneered by Inflection and recently seemingly similarly done by Adept.

The latter shifts the capital burden from Money Printing Machines (Big Tech/large academic institutions) to Money Incinerating Machines (venture capital firms), resulting in a ton of raised capital over many years ahead of technology readiness and a fair bit of dilution along the way, but possibly more defensible companies.

Research Groups → Startups: Old vs. New Paradigms

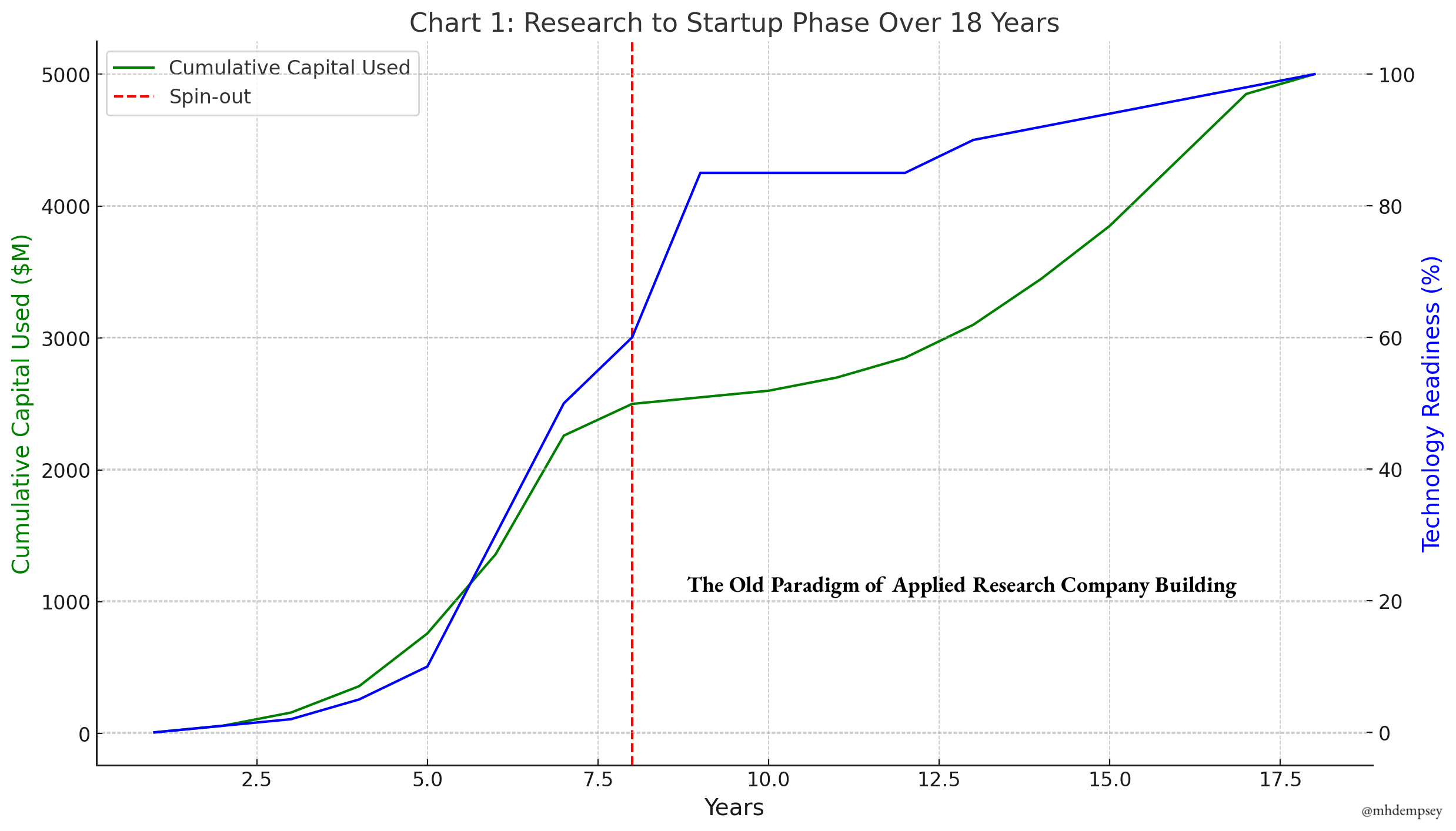

One can chart this dynamic simplistically to how research spin-outs have traditionally happened, with research groups progressing a given technology’s readiness1This is a very fuzzy way to frame this, I know while being slightly slower in progress and slightly more capital intensive, but subsidized by revenue or donations (bigtech/academia).

The spin outs typically happened as an inflection point of readiness/performance occurred and as investors were willing to underwrite “execution risk” versus purely “science risk”.

Put simply, the technology was more mature and the dollars to get it to production were split more evenly between those funding R&D and those funding Companies.

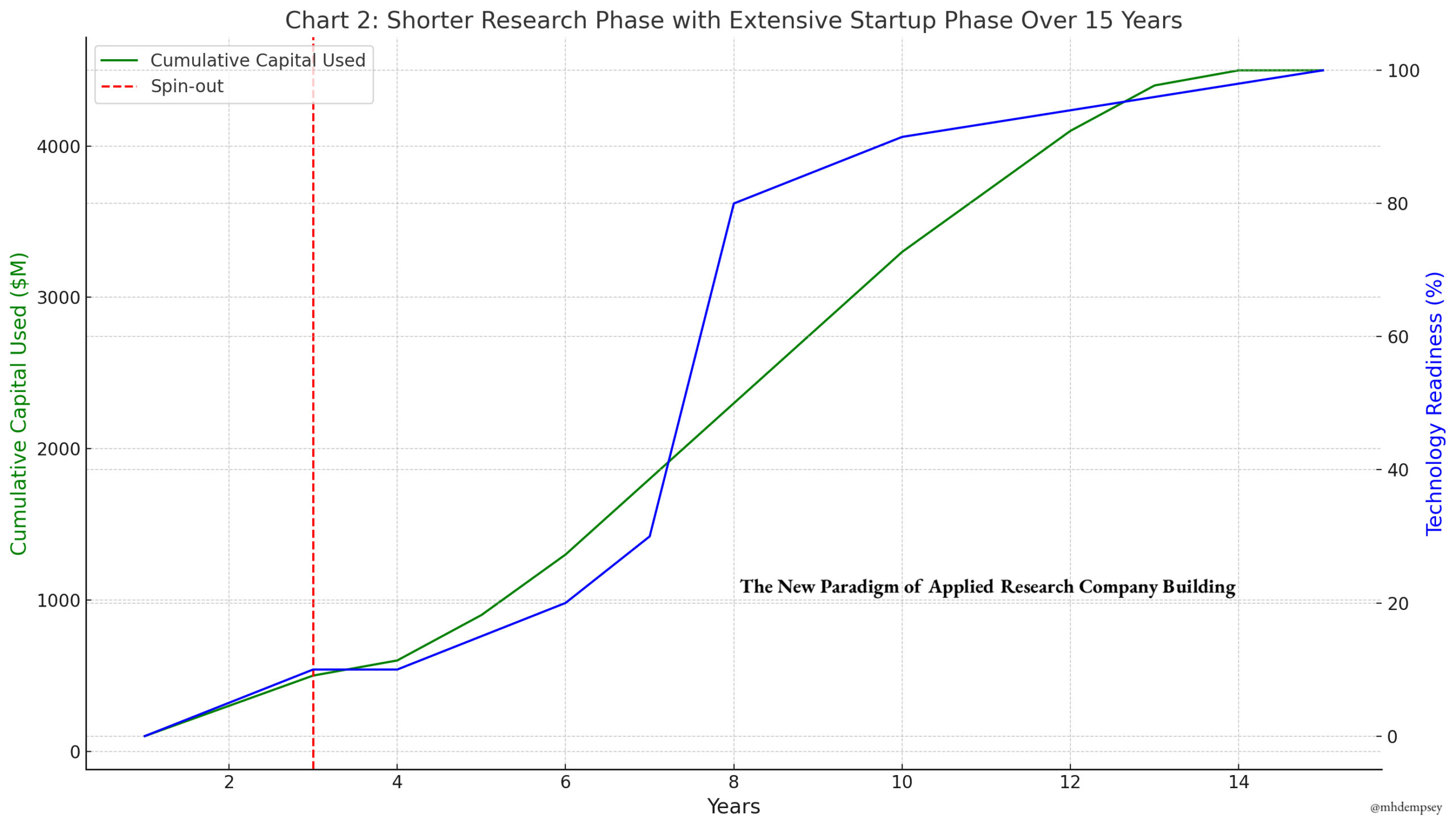

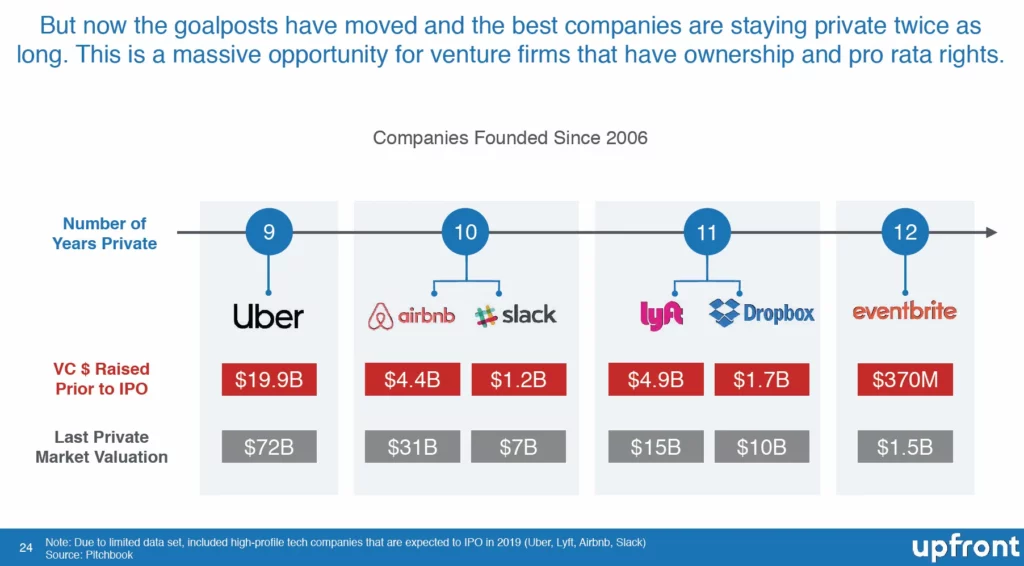

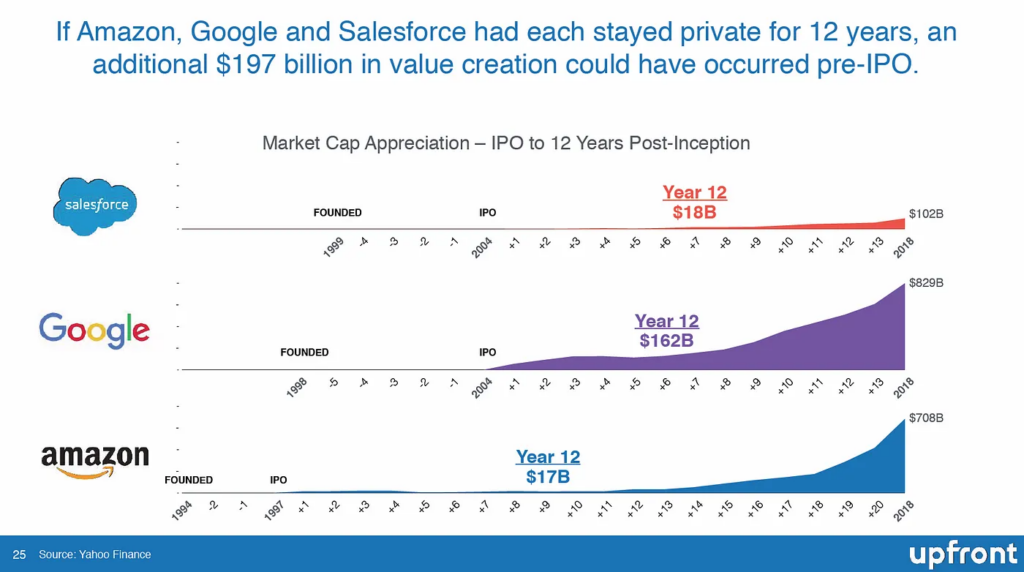

We then can look at today’s paradigm where a small amount of technology readiness is quickly spun out and funded privately, resulting in large amounts of “value capture” occurring in startups.

I covered some of these examples in my prior post in robotics, but we are now seeing this happen amongst a variety of smaller research groups across many different areas of science.

Researchers see each other’s work at a given conference over a few year period, experience a prisoner’s dilemma, raise venture money, and go to war doing almost pure research, funded by dilutive dollars in an effort to out-innovate their former employers and peers, and candidly in some cases, stave off any regret they would have if they stuck around their research lab and didn’t start a company.

The Acceleration of Research Capital

There are a few things we believe at Compound about the interplay between research labs and startups.

- Focused teams move faster, and thus startups are better at creating progress in areas with high uncertainty.

- Speed is one of the most important dynamics when building an applied research org, and rarely does money create speed in the earlier parts of technological readiness.

- If you thoroughly enjoy the pace, structures, and goals of research labs, you probably shouldn’t be a founder

- A small subset of investors understand the dynamics of building companies like this across stages (from talent composition to proper milestone planning to broader market interpretability and much more) and it is important to have those people on your board and close to you. This is what we do at Compound.

- The time between research and commercialization is collapsing at a rate far faster than many appreciate

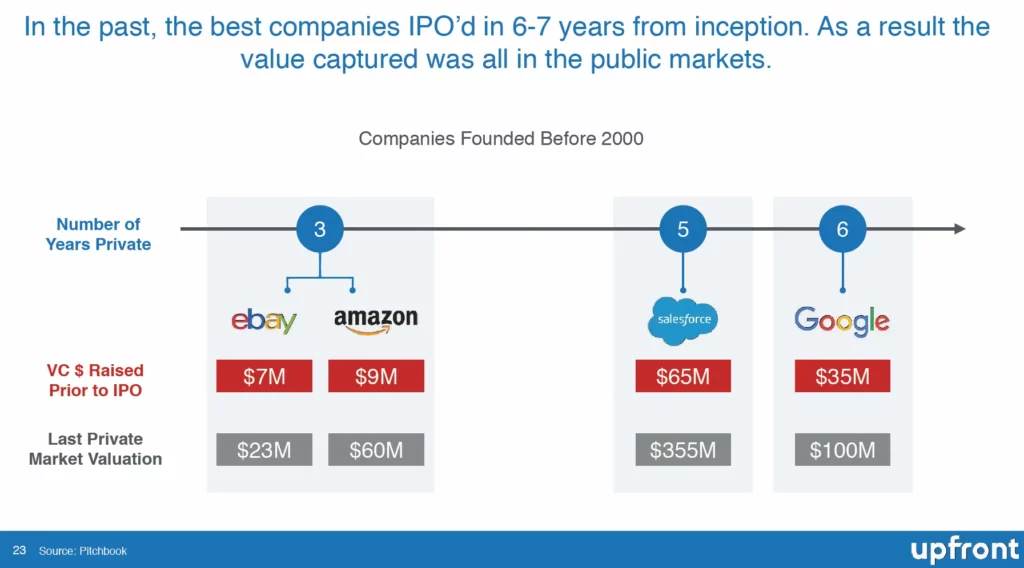

I’m reminded of this post from Mark Suster many years ago talking about the transition of public market value capture to private market value capture.

In that scenario, a large number of investors shifted down into private markets, eschewing underwriting traditional at-scale GAAP-approved financial metrics and instead moving their model to projecting compounding and extrapolating single data points into many data points.

They naturally overextended themselves but the trend line was clear and economic models of the venture industry didn’t totally break as early-stage investors also were taken care of with deep secondary markets arising.

This shift forced a change in venture firm dynamics where we saw a polarization of firm strategies with most choosing either large-scale platform firms with $1B+ vehicles or boutique early-stage firms with <$150M vehicles.

Left over were a subset of firms with what the market would deem “sub-scale” vehicles betting on their decade+ of elite returns and strategy to persist regardless of what their competition did.

In research, an acceleration has happened with later-stage VCs eschewing underwriting early or scaling product-market fit (and being more hard-nosed on what makes a post-PMF company) in service of backing great people pushing forward novel technology with low-to-medium technology readiness.

We’ll likely see an overextending once again but the larger portion of “science/research value” will accrue to purpose-built entities instead of R&D groups in a similar way that private markets have moved to capture more of tech’s market cap.2Whether the *terminal* value capturers aren’t just big tech once again, is a different question

This will likely have implications on how people build their venture firms as well, starting with the always first idea of simply using scale to throw money at the problem (buying GPUs) and progressing to a variety of experiments that may or may not work.3A post maybe for another day or that maybe will be told through the story of Compound

A Different Kind of Prisoner’s Dilemma

While these simple charts make a variety of arguments for and against what we think is optimal in company building, I’m left wondering if at times the venturification of research creates unhealthy dynamics in startups.

Talent fractures too quickly, wheels get re-invented across companies that share minimal learnings or information, and far too little patience and understanding from capital markets results in large-scale deaths of startups destroyed by overzealous investors (and founders).

This will have implications on science, as hyper-fragmentation will slow progress temporarily4but still faster than it all just sitting in labs before the waves of death concentrates talent and capital into the core 1-3 Applied Research Companies in a given area that benefit from the virtues of capitalism and competition and thus re-accelerate progress in a given area.

These are important reflections but regardless, funding will continue to seek companies and founders will continue to serve those dollars in need. A familiar story where institutional capital has become addicted to innovation, and perhaps innovation has become addicted to institutional capital.

This means at Compound we find it best to spend our time continuing to hone our craft in understanding how one should optimally build Applied Research Organizations in order to help our founders accumulate advantages amidst increased competition.

Competition from a paradigm in which maybe investors are the ones left playing chicken; staring at each other, seeing which one will deploy money into what used to be a problem ear-marked for research dollars first.

A different kind of Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Recent Comments