This post connects 2-3 seemingly disparate ideas that have meaningful implications for company building, investing, and competitive market structures. Each section could be read independently but the connectivity of these ideas is equally as important to appreciate how and why these shifts matter moving forward.

The best startups in emerging categories often act as Narrative Schelling Points. We can call these, Schelling Point Companies.1The term “Schelling point,” named after Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling, refers to a solution that people tend to choose by default in the absence of communication because it seems natural, special or relevant to them.

Schelling Point Companies do not merely sell a product or a service, but uniquely also sell an idealogy. They often are built from the beginning with less clear mid-term product views but a clear goal to serve as a focal point, or a Schelling point, of their respective categories and idea space. Their go-to-market (GTM) strategy and product are less solidified, and more importantly are vessels to dominate the narrative and use that as a mechanism for short to mid-term accumulation of capital, talent, and brand value. This all then hopefully feeds into a loop of faster and larger scale customer willingness-to-try and a better navigation of the idea maze as the category develops. Schelling Point companies inherently aim to create dominance and trust via brand in conjunction with a product, but not purely via product.

While many could say these types of companies have existed for long periods of time2Perhaps IBM is the original Schelling Point company with a focus on enterprise computing, there is a difference between building a defining company as a result of execution versus a company built around the idea of being a Schelling Point for a new technological inflection point or societal shift.3AirBnB and Uber were built around the idea that fixed assets were underutilized, however neither focused on the core idea in order to dominate the movement versus a very opinionated view on the best products to build under that thesis to dominate their given vertical and replace incumbent solutions (hotels / taxis).

This dynamic is especially relevant in emerging categories where the market and technology potential is yet to be defined. Schelling Point Companies attempt to own the novel category (that they help popularize and at times, create) and build an Idea Moat; a mechanism we talk a lot about at Compound that results in a dynamic where people who speak about a given technological or societal shift must mention a given company, else sounding uninformed or intentionally avoidant.

Schelling Point companies shape the way users, investors, and talent perceive the category and set the standards and expectations that future entrants will have to disprove and/or exceed in order to overtake the original company narratively. They are often first movers in a given area and have more horizontal/full-stack ambitions than most startups.

Founders of Schelling Point companies are very high conviction that something under-appreciated will happen but want to build an organization that can be malleable because of mid-term uncertainty into how to precisely make it happen through sequencing. Typically these visionary founders/CEOs are best paired with operational excellence in the executive team as the companies scale in order to push on the advantages of narrative while the COO/President/Co-CEO/etc. maintains operational discipline.

Examples of these companies include Palantir in government tech, Anduril in defense tech, OpenAI in frontier AI, Ginkgo Bioworks in Synbio, Recursion in computational bio, Bitcoin in crypto, Physical Intelligence in robotics, and more. Once these companies awaken talent and capital markets to an opportunity, they then see a ripple of fast followers4Labs like Mistral in AI, Rocket Lab in Space, and many more in areas ranging from computational bio to synbio to robotics and a birth of adjacent opportunities that were slightly out of scope for the company.5A repeat pattern of this is bits to atoms progression, like Palantir to Anduril in the “new defense contractor” space and OpenAI/Deepmind to Physical Intelligence as a domain transfer of idea from frontier AI labs to Robotics and Embodied Intelligence

Fail States for Schelling Point Companies

Being a Schelling Point company creates an incredibly powerful position on the upswing for all the reasons mentioned, but also can lead to false feelings of momentum that can either come from investor interest being mistaken for progress, customer churn being under-appreciated/hidden by lowered difficulty in customer acquisition, as well as talent flows masking broader cultural/team problems. These are all versions of crises of overconfidence.

While the blast radius of a failure of a company typically is contained, when a Schelling Point company collapses, it can often effectively destroy a category for years to come (as companies like Ginkgo and Zymergen candidly did for SynBio the past few years).

P/R Ratios & Narrative Leverage

The thin line that founders walk when building a Schelling Point company is accompanied and articulated well by Kwok’s September 20216What a perfect time post on Narrative Distillation. In it he discusses price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios and Perception-to-Reality (P/R) ratios of startups.

Narrative leverage in tech is most commonly understood in the sense of Steve Job’s Reality Distortion field.

Narrative Distillation, Kevin Kwok

Personally, I like to think of this narrative leverage as a form of PE ratio (Price to Earnings ratio). I sometimes call it the PR ratio (Perception to Reality ratio)…

Thus Tesla’s PE ratio is in many ways self-fulfilling. If Tesla could get people to extend the access to capital it needs for long enough it will be successful. If it could not, then it would have collapsed. Ironically, this means that far from Elon’s antics being distracting, his ability to maintain these high PE ratios might be the most important driver of the company’s ability to succeed.

But this general concept is not unique to the public markets, or to money. In some sense, even people have a social capital PE ratio. PE ratios in the public markets are just one instance of a more general concept of having some view of what something can become—and giving them today the benefit of that future tomorrow accordingly.

Narrative leverage is the PE ratio of a company. Not just for cheaper cost of future capital, but also for everything else companies care about too. Cheaper cost of recruiting, customer development, and perhaps most importantly—internal coordination.

High “Price-to-Reality” ratios often coincide with periods of technological upheaval or abundant liquidity (or both).

As the venturification of research continues to progress, Schelling Point companies likely will attempt to be created at a far higher rate due to the strategy being perhaps a default state for technical organizations with large amounts of talent and high level concepts, but fewer strong views on value capture.

What’s perhaps most interesting is how this creates a feedback loop. As more research transitions to venture-backed entities, the need for narrative leverage increases, as these organizations must justify their capital intensity and timeline uncertainty. This in turn leads more companies to attempt to position themselves as Schelling Points for their respective breakthrough areas, hoping to accumulate enough narrative capital to buy the time needed for technological development.

We’re likely to see this pattern accelerate across many different emerging technical categories as AI creates breakthroughs, as well as across societal shifts driven by geopolitical or other types of instability or volatility.7At Compound we believe biosecurity is ripe for this, for example

On the steep uptrend before peak fervor is when we see the highest P/R ratios of companies, exhibited by quickly escalating valuations as fundamentalism turns to momentum and the greater-fool theory of investing.8A great example of this today are the variety of OpenAI spinoff labs that are raising pre-product at multi-billion dollar valuations. This momentum can be externally driven by the market or intentionally driven by the company itself.

It is important to remember that becoming a Schelling Point company is not a passive process. It requires a deep understanding of the market dynamics at play and a recognition of what drives your company’s P/R ratio (team, technology, product, market, etc.) and its ability to maintain these high ratios in order to thread the needle between perception and reality.

Building a Schelling Point company is not particularly about building public narrative.

When I think about successful Schelling Point companies, they typically have an ability to know when to seek broad versus specialized propagation of their narrative. As the tech industry continues to appreciate the value of narrative, many founders over-rotate on the desire to seek fame or thought leadership too early on in the development cycle of their company.9This can be both as a means to drive interest in the company or to create a hedge by building a large personal brand. Or it can start as one and end up as the other. Privately, many people will notice (and talk about) when a founder’s timeshare drifts from execution to what can be perceived as clout chasing or kingdom building, and publicly it can quickly put pressure on the P/R ratio if a given leader is seen as equally concerned with twitter as they are with execution ahead of product-market-fit (PMF).10I add this caveat as I do think there are times in which CEOs jobs do move far more towards vision, recruiting, and marketing, and that being online may be a correct strategy. I don’t think it’s pre-PMF though.

In fast changing areas, execution also requires a certain level of agility, as startups need to be able to adapt and evolve as the market changes and new information becomes available. We are seeing this over and over again within AI and points to what I’ve talked about before with respect to OpenAI’s potential core competency:

While I’ve laid out a potential bear framing for OpenAI (scale, money, data underpinned by transformers is all you need, until you don’t) a perhaps hyper-bullish take is that as an organization they have created the machinery that is best at exploring and scaling model development, and this has bought them time to continue developing into an increasingly competent product organization.

Speculation Progression & Capital Accumulation

Schelling Point companies have historically been treated as isolated entities that accumulate capital and perhaps spin off/accelerate the creation of competitors, but largely get built within private markets and have isolated impact. What is under-appreciated is that in recent history they have also been exogenous shock creating machines in public markets.

Over the past few years as market participation has meaningfully expanded globally we’ve seen a shift to more narrative-driven investing as retail participation has increased and demographics of institutional investors have changed. I’ve covered this topic ad nauseum in prior posts including Speculative Bubbles in the 21st Century & Asymmetric Upside and Get Rich or Die Tryin’.

Because of the mainstream nature of startups today, some Schelling Point companies also have far more reach than ever before, infecting the mind and dominating the narratives of speculation-hungry investors. These investors look first for fundamentally-driven companies to invest in a theme and progress all the way to speculation-driven ways to get what they deem “pure play” exposure either to some derivative of fundamentals (sophisticatedly referred to as ShitCos) or derivative of narrative (Meme Assets).

If so much of markets have become “one big trade” then people look for assets that embody “one simple theme”.

In Robotics FOMO, Scaling Laws, & Technology Forecasting i walked through this progression of speculative layers with the AI trade as capital progressed from hyperscalers (easy to understand but not pure play) and Nvidia (easy to understand, effectively viewed as pure play) to infra providers (harder to understand, but “more” pure play than hyperscalers).

We are now beginning to more loudly see this same paradigm at scale propagate to application layer companies as we start to see AI productization progress. This will create whipsaw effects in markets as people first take fundamentally-driven views, but if they are unable to find them, then move towards more narrative-driven assets.

We’ve seen this on the fundamental side for companies like Duolingo and on the narrative side for companies like Aurora or potentially SoundHound with well-run companies like Palantir being somewhere in the middle as they trade at short-term irrational valuations due to narrative premium.

These shifts also can have negative fundamental and narrative impacts as well, as we’ve seen with companies like Getty selling off materially as Midjourney and diffusion models entered the zeitgeist in 2023, as well as most recently Nvidia experiencing a sharp decline upon the release of Deepseek’s R1 model. 11There are many other examples to walk through here and is also why investing long/short in 2025 is perhaps more interesting than ever before in my career

When a given micro-narrative (and thus basket of companies) begins to run out of exhaust, we see capital rotations towards even more speculative assets in order to squeeze more and more juice out of the simplistic viewpoint that market participants convince themselves is mispriced relative to the rest of the market psychology. These perceptions of mispricing are in my opinion more reasonable to believe the farther out you get from pure first-order effects, as they inherently carry more cascading layers of future speculation that is difficult to “price in”.

Multi-Narrative Assets

Unlike in the private market examples given above on adjacencies, there are also times in which the best companies continue to serve as Schelling Points for all the adjacent narratives they help create or could take advantage of.

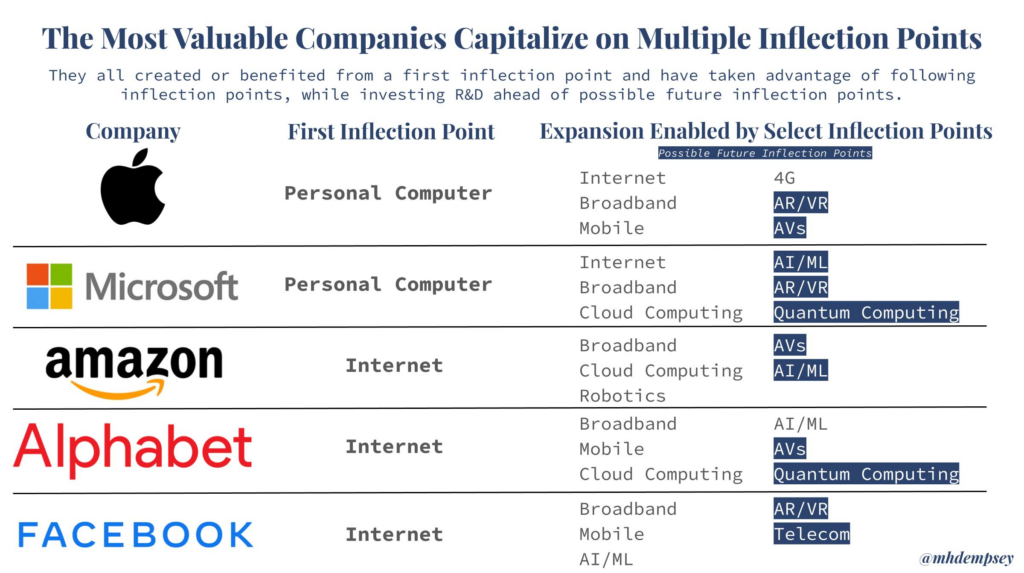

We have seen this with hyperscalers repeatedly being very good at capturing the given major technological inflection points and extracting massive value from the past decade due to their ability to plow large amounts of capital back into R&D.

However, no company has more precisely navigated being a beneficiary of multi-narrative assets as Tesla. Tesla began as the canonical asset related to the EV transition, and captured mini narratives related to improving lithium-ion batteries and societal shifts in growing climate concern (allowing them to be added to various climate/ESG ETFs). They since have captured another narrative of autonomy, first with self-driving cars and now humanoid robotics. There is no greater narrative creator than Elon12except maybe sam?!, regardless of how much defensible value he does or does not create within Tesla.

Tesla’s positioning as a multi-narrative asset is a sibling to the idea of the Ponzi Scheme of Ambition in which companies “keep highlighting their entry into larger and larger markets and so investors keep ponying up $ for the ambition”.13I walked through Uber as an illustrative example in Narratives & Pseudosecrets

While on the surface this concept feels somewhat absurd in an efficient market (and I sometimes add to that stupidity like when I half seriously opined about Japanese software companies), these dynamics continue to persist in how companies position themselves both explicitly and with “soft signals” of trying to use their brand position to take out weaker narratives. There will be more companies (like OpenAI or more recently in the news, Tempus) that represent similar technological inflection points and will capture capital flows due to their ability to represent multiple core themes.

When Narratives Seek Assets

Disruptive technological narratives most often get propagated from private markets to public markets over some period of time. When tech was not so heavily covered and wasn’t the main thing this meant the pace in which this happened was slow, and awareness typically was less important to public market participants until many years post-breakthrough.

The early sign of this changing was when hedge funds began to come down to venture land and write checks into pre-IPO companies.14This was as much about technological change as it was about market forces leading to more value capture happening in private markets This progressed to hedge funds becoming “crossover funds” that did both venture and public market investing with a different promise/value-add to founders15That promise ranged from “we can help you get public and will hold your shares!” all the way to “we will pay more than anyone and don’t care about diligence!”, and in theory has led to a tighter coupling of these skillsets as large AUM firms must capture both private and public market value creation in order to sell the story to LPs/generate outsized returns.

At the same time, we are in the early (middle?) stages of a technological wave that has the entire industry (world?) reckoning with a realization that AI could be as disruptive as it is enabling with fairly low consensus on where or how value accrual happens. As we have said in many letters, posts, and presentations, perhaps the prior decade of tech was about market cap expansion of technology (tech eats the world) while the next may be about incumbent destruction (tech destroys tech). This has led to a collapse in the time, as well as an expansion of value creation/destruction that these narratives impact public (and private) companies.

A large amount of capital trying to understand how to express their views against a small number of narratives in order to squeeze out minimal amounts of alpha (or levered beta).

what happens when investors are unable to find assets to express these ideas and speculate on important narratives?

It used to be that as narratives would proliferate throughout markets people would look for derivative companies that still had fundamental underpinnings to express some sort of financially-driven view on the narrative.

In 2016 when Uber and the On-Demand Economy movement was reaching its crescendo in private markets, many public investors were long Twilio post-IPO as a pseudo-derivative due to their customer concentration as well as the fact that their mobile infrastructure could be seen as a core pickaxe and shovel to the movement. This swung both ways as investors could argue the long case for Twilio on the expansion of Uber-esque opportunities all driving outsized revenue growth, while others could argue the short case due to high customer concentration.16The bull case was more right, though notably a few years post-IPO the stock sold off ~30% on the news that Uber was moving their business away from Twilio

This echoes how some discuss Nvidia today.17Though luckily this time all the main customers pretty much have signaled they will yeet into oblivion for Nvidia chips Today, Jensen seems hellbent on trying to diversify both perceived markets as well as parts of the company stack as shown by the company’s aggressive public announcements of new partnerships seemingly weekly across every possible vertical, alongside previews of more GPU-enabled end products.18Perplexity is an interesting example of a company that also did this approach but as a means to juice customer acquisition because the switching costs of search were so high for users.

As markets mature, so do the best public company leaders in managing the psychology of investors. More broadly, as Kwok highlights in his post, the best founders know how to keep their P/E ratios high for as long as possible, and in Jensen’s case one could argue Nvidia needs to do so in order to withstand any demand or regulatory shocks, all while hoping their diversification allows non-LLM bets to pay off and close their P/R ratios over time.

Narrative Receptacles

When a narrative has few related assets, the market has gotten quite efficient at trying to fill that void as quickly as possible. We saw this with Deep Tech oriented SPACs in the 2020-2022 bubble as everyone positioned their SPAC as the best “pure play” opportunity in an effort to drive retail flows as well as outsource their marketing to ETFs like ARKK or ARKQ (who then get to drive retail flows) to aggregate these narratives.

I call these companies Narrative Receptacles because in their end state they are supported by and exist primarily to absorb and contain market psychology around a given theme.

Many reasonable people may believe this dynamic largely died with ZIRP-times because how could anyone continue to buy into slides like the ones above when they weren’t going crazy from being trapped inside their house for 8+ months straight.

They would be wrong.

As an illustrative example I would invite you to look at Serve Robotics ($SERV) which is currently valued at $1.1B and had $1.91M of revenue in 2024. I would speculate that Serve has been a beneficiary of the awareness of Robotics as The Next Big Thing, as private robotics companies continue to raise at multi-billion dollar valuations in private markets less than 12-24 months after founding.

While these companies are only available to a small subset of private investors, Serve is a nice pure play robotics company that claims it’ll go from 59 to 2000 robots deployed in 12 months and also recently described their sidewalk delivery robots as bringing level 4 autonomy to market and “unbundling cars” in addition to commentary on their climate impact and a drone delivery partnership. The company also has a partnership with Nvidia it touts heavily. It is up over 300% post their reverse-merger in April 2024.

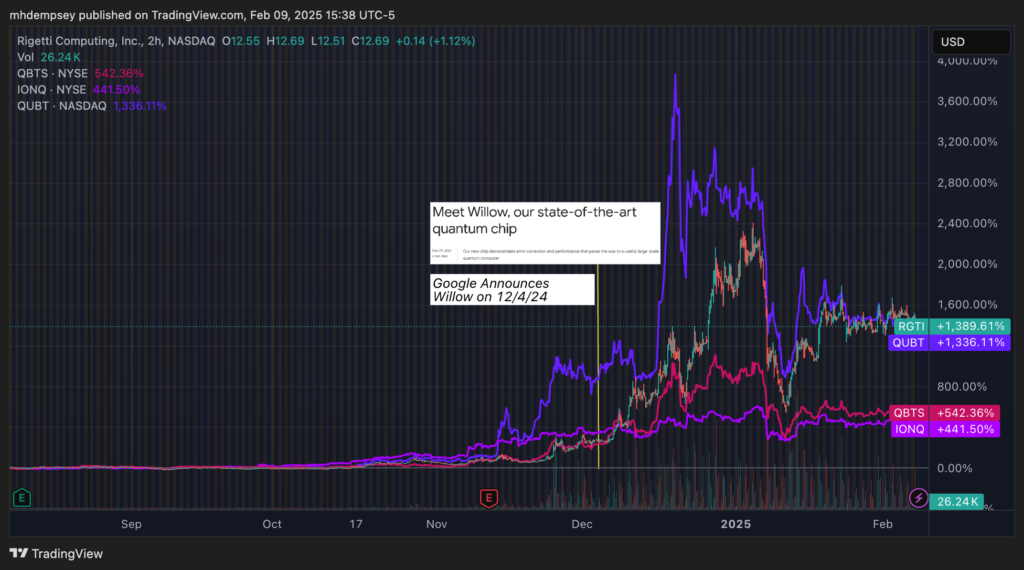

The increased interest in quantum computing stocks are another example of this dynamic in which a somewhat hyped technical breakthrough announcement19that smarter people than me would say was not actually that big of a deal from Alphabet led to an increased focus in quantum computing as a category and a basket of assets that was previously effectively left for dead all rallied 4x-10x+ in a few months.

This phenomenon explains why perhaps marginal or clearly subpar assets still find capital; the market wants to create more financial instruments to chase any lingering upside.

These attempts to capture narrative premiums without the underlying technological progression create predictable dislocations. However, while private market Schelling Point companies often have years to navigate their idea mazes and develop product and a GTM to grow into their P/R ratios, public market companies face quarterly scrutiny that can quickly and aggressively reveal the delta between perception and reality.

For investors who can parse the difference between companies truly pushing technological boundaries versus those merely drafting off narrative tailwinds, these dislocations present compelling opportunities.

The Crypto Microverse

A way to think about the crypto market sometimes is like a microverse inside the universe of normal markets with amplified risk-taking and compressed speculation time horizons for the vast majority of market participants.

The crypto microverse has both its own narratives as well as derivative or translational narratives. These narratives can start from traditional tech markets and intersect with crypto principles to (in theory) create novel companies/projects/protocols that are more likely to win with token-enabled models and/or are better long-term models when decentralized versus their centralized/off-chain counterparts.20Compound invests with a collection of theses against this core view.

The original impetus of this post started from a single Smac tweet that tells a good story about where we are today in one of these areas: The intersection of crypto and AI.21Thank you for ruining my Saturday, Smac

As AI entered the zeitgeist, the cryptosphere struggled to effectively capture and capitalize on this narrative shift. The fervor for speculation grew so intense that the microverse not only sought out new assets but began retrofitting existing protocols with AI-adjacent narratives, regardless of merit.22The darkest part was when all the crypto traders started to talk about NVDA options trading

Private markets got to work, funding a variety of effectively (or actual) scam venture-backed projects that carried minimal real technical merit/value creation but great narrative potential if you didn’t ask any questions surrounding compute, ai models, data aggregation, data infrastructure/cleaning, on-chain agents, and more.23This is the part where I have a disclosure that Compound is an investor in Prime Intellect as well as another stealth AI x Crypto project.

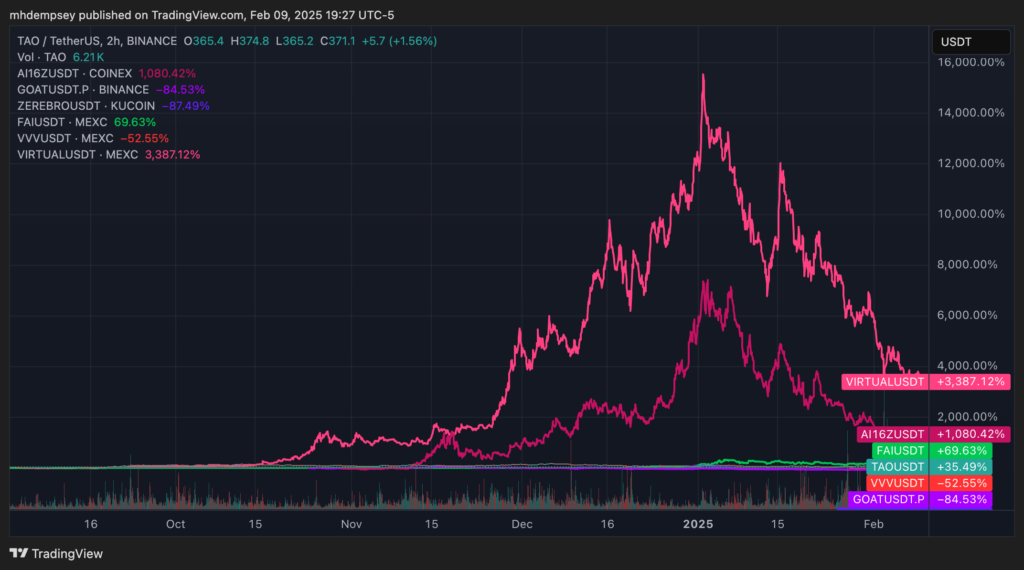

As these rounds were announced and AI continued to garner attention, the cryptoverse hunger for exposure to this theme increased and the only buyable pure play asset was effectively Bittensor ($TAO), a protocol which today describes itself as “an open source platform where participants produce best-in-class digital commodities, including compute power, storage space, artificial intelligence (AI) inference and training, protein folding, financial markets prediction, and many more.”

We can call this the “kitchen sink” approach to narrative building.24There is perhaps an argument to look at the progression of company positioning and if it gets more kitchen sink over time without progress, as TAO did, it likely means thrashing and rudderlessness.

$TAO quickly was recognizable as the Schelling Point project for Decentralized AI and it swiftly rose from ~$50 to ~$710/token in about 6 months, peaking at north of a $15B fully-diluted-value (FDV).

As the narrative increased, markets continued to fill the void with assets attempting to displace Bittensor for the AI x Crypto narrative supremacy. Bittensor was hard to understand (and candidly increasingly unimpressive as the product became legible) and thus a thousand easier to understand projects were born, ranging from GOAT (a memecoin for an AI account called Truth Terminal funded by an andreessen grant!) to ai16z (an ai investing bot!) to Zerebro (an ai artist!) and much more.

Due to the entire category of assets being narrative-driven (and not fundamentally driven), $TAO lost $4B in value in about a month as capital fled to better pure play assets with lower entry points. With AI x Crypto at its peak fervor ending 2024, many of these assets launched, rose to absurd valuations of hundreds of millions or billions of dollars before crashing down aggressively just weeks later.

When there are no fundamentally driven assets to speak of, one must recognize the dynamics that drive flows in and out as well as the fragility that narratives can possess. Price-to-Reality ratios can collapse very, very quickly.

Repeat Bubbles

Owen Lamont at Acadian recently wrote a post about the repeatability of bubbles (which was to my dismay targeted at Bitcoin). In it he discusses various reasons why bubbles may repeat, including new investors entering the market, winners of the bubbles pushing their luck, external forces such as government or technological shifts, and social media (”a hothouse environment for ideas to spread across the investor population”).

The core point Lamont somewhat intentionally avoids, in his focus on Bitcoin, is that the repeatability of bubbles isn’t confined to a single asset class. It’s a systemic phenomenon, amplified by the very forces that drive the creation of Schelling Point Companies and Narrative Receptacles: the search for narrative, the desire for pure-play exposure, and the expansion of market participation. Whether it’s tulips, dot-com stocks, crypto, or the next emerging technology, the underlying drivers of these cycles remain remarkably consistent and the human behaviors often result in the price action of these patterns looking similar.

The key, moving forward, is not to predict which asset will bubble next, but to understand the conditions that make bubbles possible and to position oneself accordingly, both to capitalize on the upside, to protect against the inevitable downside, and to test or establish conviction far before consensus, or explicitly in the ruins of over-exuberance.

Moving Forward

A consistent theme I’ve observed over the past few years has been human’s increasingly aggressive speculative nature and our inability to parse signal from noise. These concepts permeate into so many different branches of our lives.

Investors bounce between levels of conviction and across narratives, talent flows between industries and companies at a higher pace than ever before, and people trade ideologies as loosely as the wind blows if the collective noise is loud enough (or the individual’s conviction is fragile enough to not want to stand alone).

As we navigate an era of accelerating technological change and expanding market participation, the dynamics of Schelling Point companies and narrative-driven markets create a recursive loop in which each new breakthrough spawns both legitimate innovation and speculative excess. This likely means these loops will continue to occur and perhaps become more violent.

This acceleration presents both opportunity and existential risk for founders building in emerging categories. The ability to accumulate capital and talent through novel forms of narrative advantage remains powerful, but the window to translate perception into reality, to close the P/R ratio gap, may continue to shrink. Those who succeed will likely be the ones who understand that narrative isn’t merely about storytelling or kingmaking, but about creating enough space and time to build genuine technological and structural company advantages.

For investors and market participants broadly, the key may not be to avoid these cycles entirely, but to develop frameworks for parsing the difference between companies using narrative as rocket fuel for legitimate innovation versus those purely drafting off of speculative fervor. After all, the most fascinating aspect of Schelling Point companies isn’t that they temporarily capture mindshare and capital, it’s that the very best of them transmute those resources into genuine breakthroughs or sequences of actions that reshape and create industries.

Perhaps then, the truest test of a Schelling Point company, and maybe of all founders, investors, and people, isn’t the ability to dominate a narrative, but the ability to survive an eventual collision with reality.

Thanks to Smac for thoughts on this post.

Recent Comments