This post is a result of a talk I gave at our 2020 Compound Annual Investor Meeting. For a video of this portion of the presentation, see below:

In recent times, the venture capital industry has reinvented itself every few years, and 2020 shined bright in that regard, with both flurrying activity as well as mass volatility. As we head into 2021, we’re heading towards a great bifurcation of venture funds, an explosion of narrative driven value creation, and much more which will meaningfully change the job of technology investors across all asset classes.

This post will walk through those dynamics and explain what happened and where we’re going in technology investing across public markets (sort of) and private markets.

COVID BRINGS FEAR & ACCELERATES FUTURES

First, we must start with COVID’s impact on technology markets.

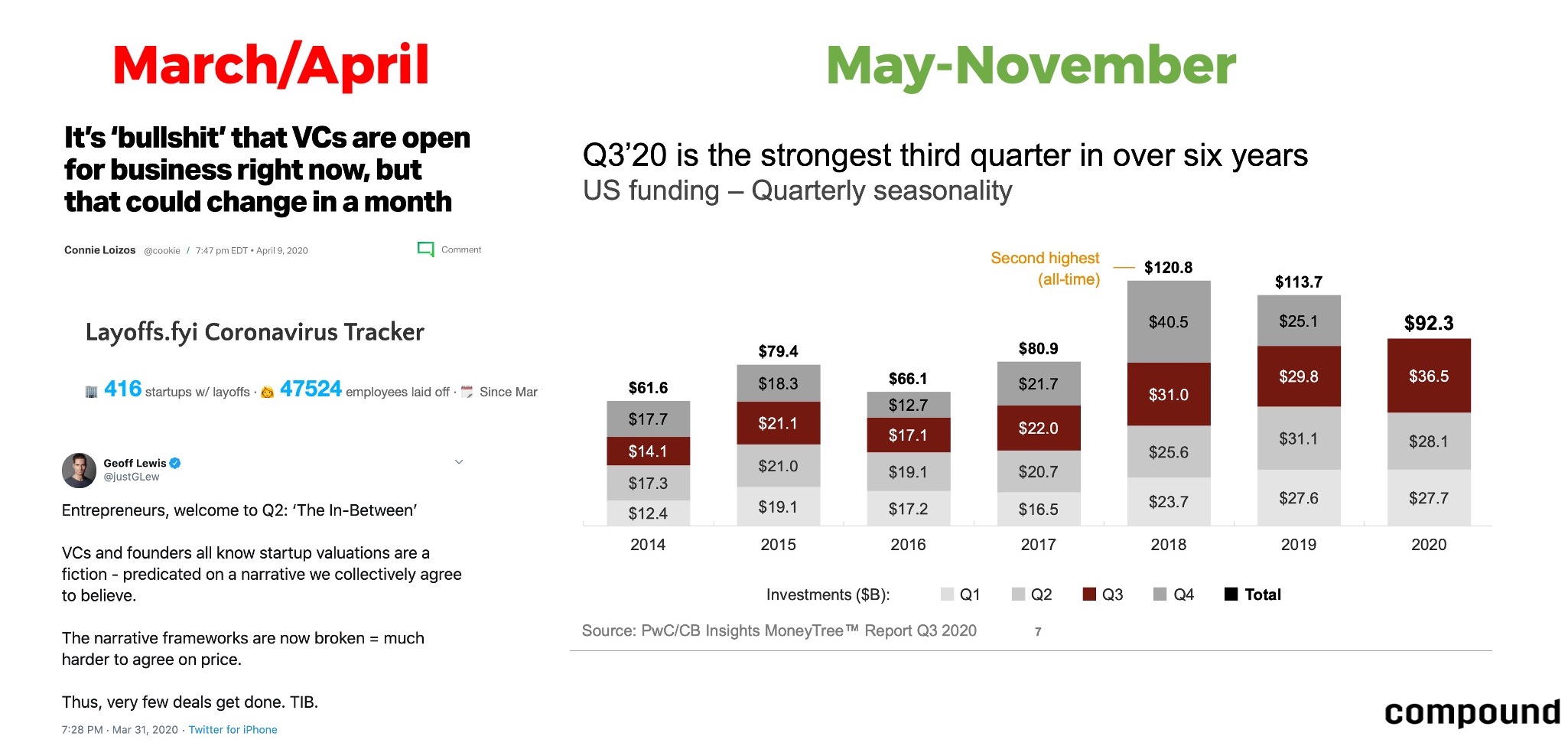

As COVID cases began to rise in the US, we saw technology markets collectively freak out, with a wave of layoffs, VC mixed messaging, a Sequoia Black Swan memo, and a resulting view that markets were not clearing.

Markets quickly bounced back1Both science as well as governments (with massive stimulus) seemed to give us a better timeline of the impacts of COVID on the economy and the possible duration of this pandemic. while COVID materially pulled forward futures that investors had been betting on and believing in across healthcare, automation, and most notably a rapid TAM expansion within software and “digital living” broadly, ranging from consumer industries like gaming to enterprise SaaS and infrastructure as our workflows shifted entirely digital.

With the entire market looking ahead to a post-COVID world, markets quickly became more about the future than ever before, and thus more narrative driven than ever before.

Narrative Driven Markets

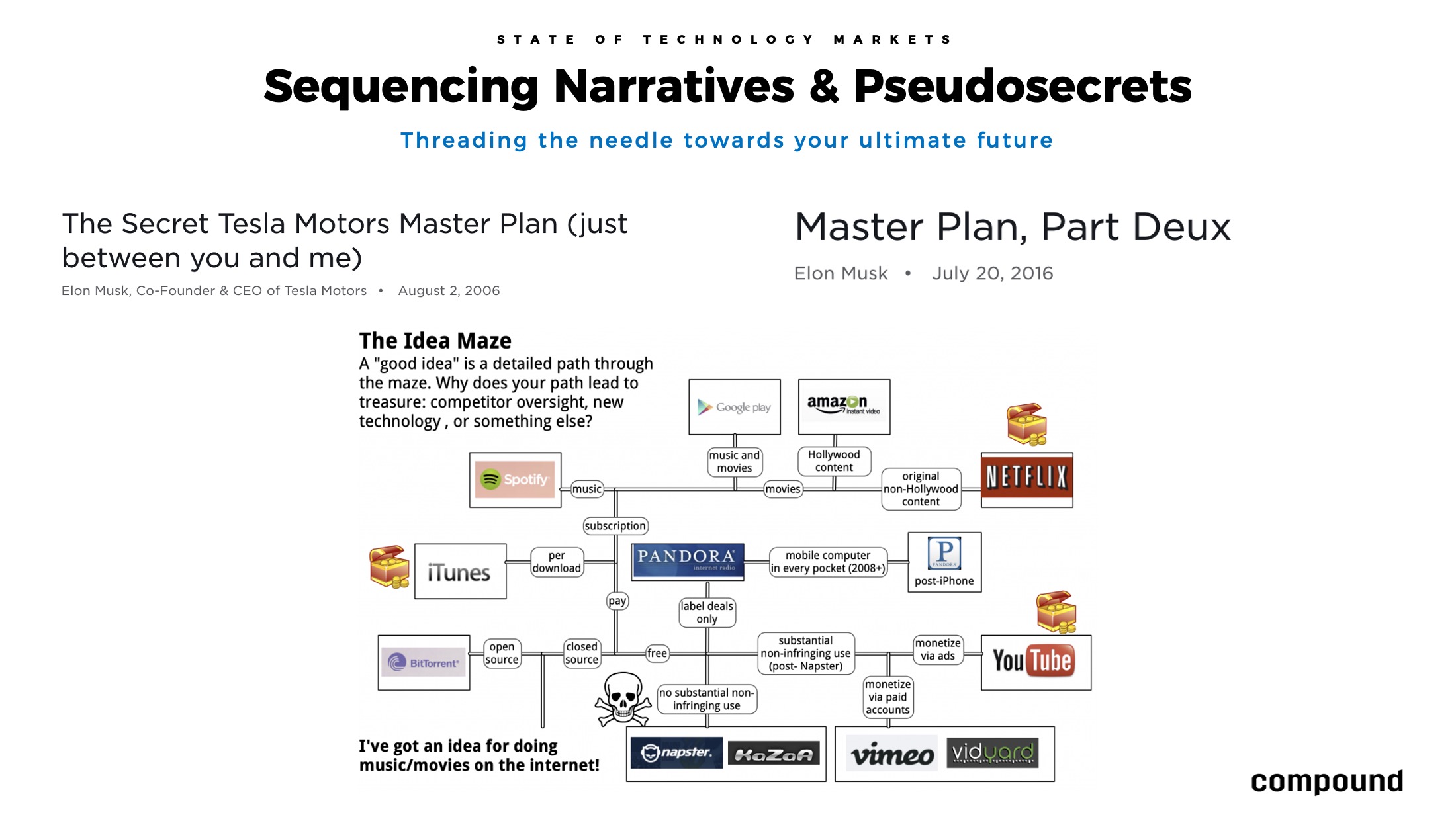

Private markets have always been dictated by narratives. I’ve written before about the power of narratives and pseudosecrets. Founders who are great at propagating narratives can more clearly make the future they believe in seem closer to a reality and convince their stakeholders, whether customers, employees, or investors to believe in and dedicate their time and capital to this future.

In deep tech areas, we think about sequencing narratives a lot, specifically helping founders figure out how to navigate the proverbial idea maze and show step functions in value creation as they thread a needle to their ultimate future.

Elon musk is the canonical example of this.

Musk has similarly done this with his company SpaceX, and their eventual goal to colonize mars and make human life multiplanetary by driving down the cost of launch due to reusability, generating substantial cash flow via a telecom network9For a very in-depth read on how important StarLink is, read this piece by Casey Handmer (StarLink), enabling a privatized and economically viable space economy to emerge (due to continual launch and relay), creating core infrastructure for re-fueling on mars, and then allowing us to further explore and/or colonize planets.

Musk always frames these sequences as a way to bring these futures forward in economically viable ways. With Tesla he said: “The reason we had to start off with step 1 was that it was all I could afford to do with what I made from PayPal.” and more recently with SpaceX, while discussing BFR and becoming a multiplanetary species he said:

However, historically once companies have hit public markets, the power of narrative has faded, with really only Amazon having benefitted from a perpetual story of TAM expansion that allowed public market investors to forgive years of negative EBITDA (something we are now comfortable with in 2020).

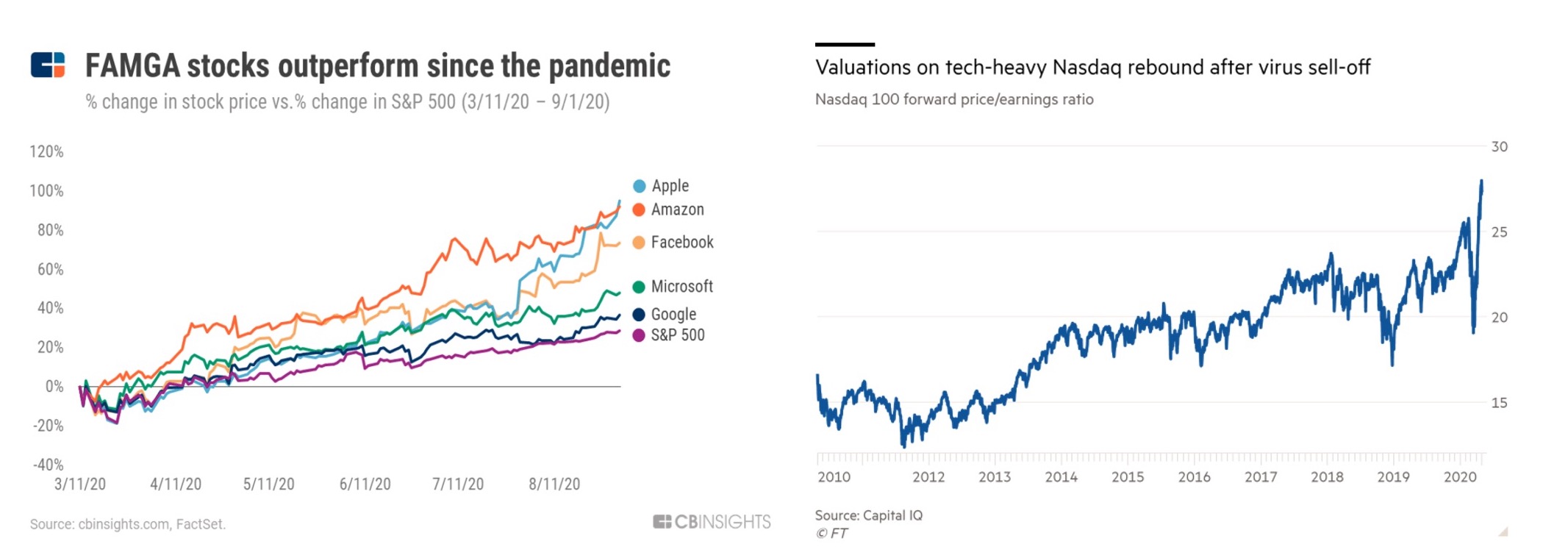

PSEUDOSECRETS BECOMING common knowledge & VALUE APPRECIATION

What we saw with COVID was that the entire market quickly realizing that they had both underappreciated the TAM for many technology companies, as well as the power and scale of these companies as our lives moved entirely digital due to lockdown and quarantine.

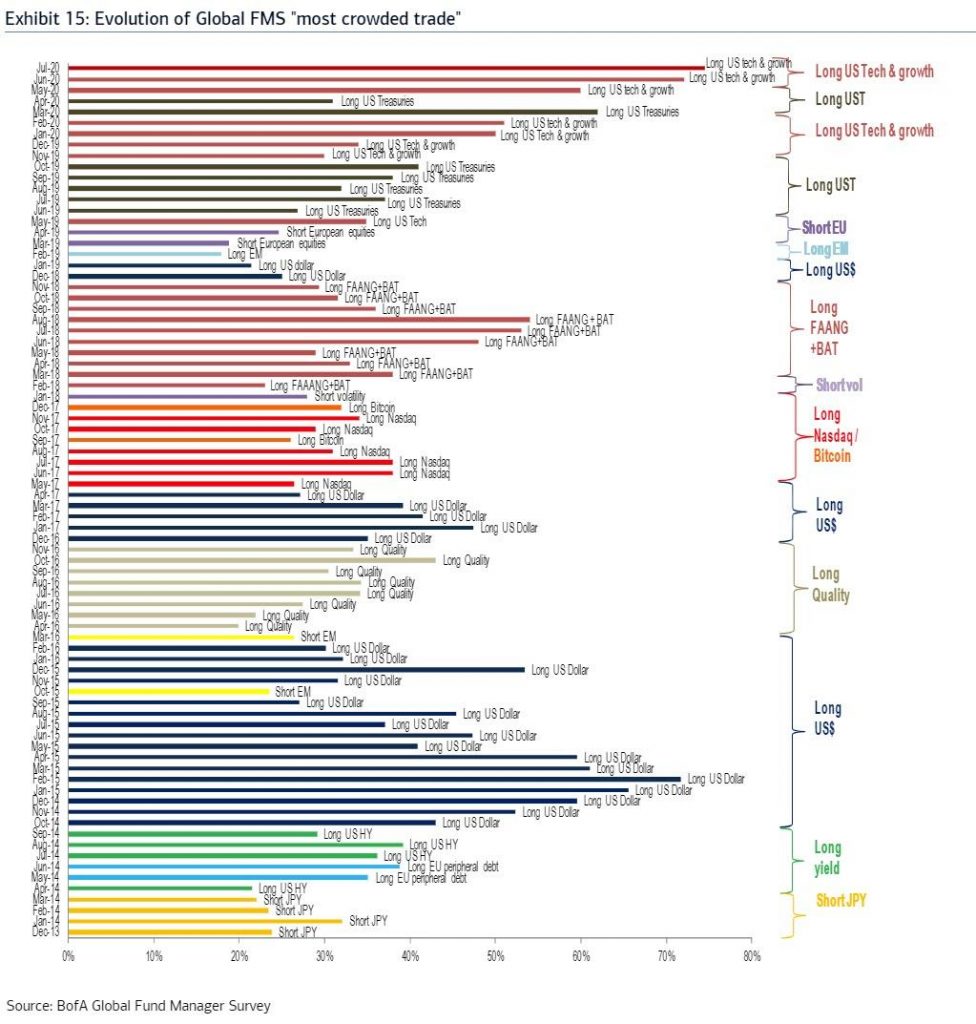

And what happens when pseudosecrets become common knowledge? Markets rally, valuation multiples expand2Some could say ZIRP leads to this as well and long US Tech and Growth becomes the most popular trade in history.

But some people knew this pseudosecret already.

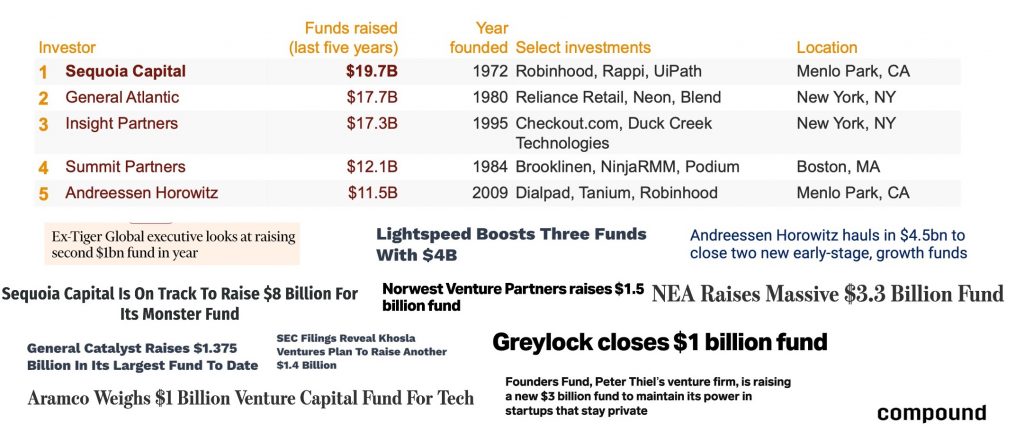

The salvo shot in this understanding was in 2011 when Marc Andreessenn famously said “software is eating the world”. He meant it, and A16Z and a variety of peers have doubled down on the view that we hadn’t scratched the surface of the value creation of technology over the coming decade. They raised multiple mega funds and one of them even raised a $100B fund.

As mega-funds stacked up, there was a lot of ink spilled writing about the rise of mega-funds, with many speculating that this was the clearest sign of a bubble…for years. But if anything, this year has validated the views on TAM that many of these firms held.

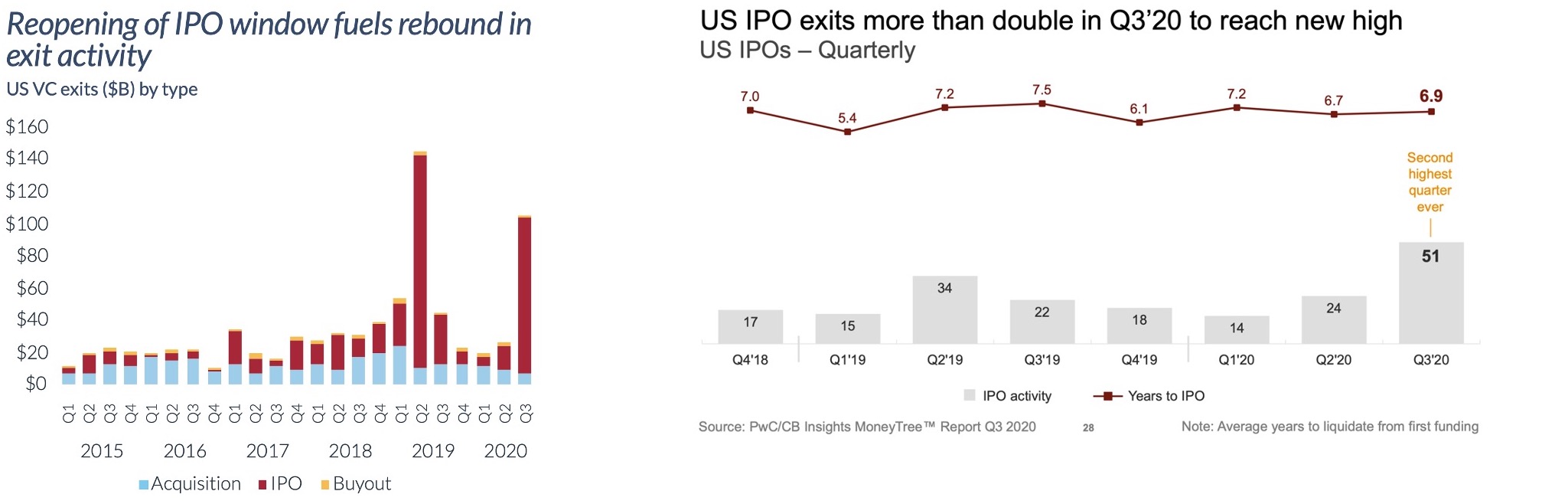

What this new narrative surrounding tech also did was open up the IPO window, giving companies that once were afraid to be under public investor scrutiny a feeling that now, finally, the market would properly value the promise of their businesses. But, if tech is now more than ever about the future promise, the issue was IPOs lacked future looking narratives and statements.

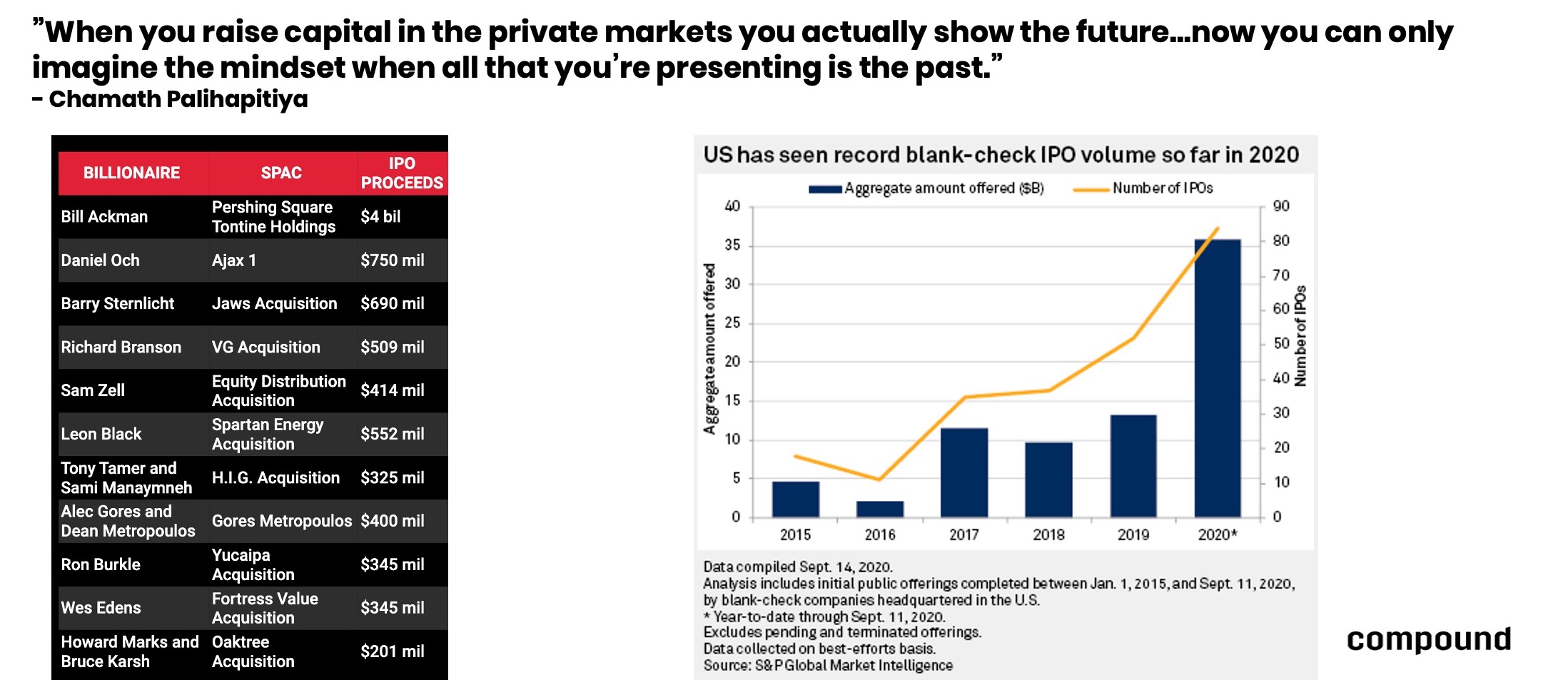

SPACs solve for this and allow companies to get liquidity while picking a sponsor who can paint a forward looking narrative to the rest of the public investors base, proliferating their pseudosecrets through big banks and Robinhood accounts everywhere.

And SPACs aren’t just for companies trying to get public faster, but it also served as a class of investment round for certain types of companies where the traditional pre-IPO investors were less well-suited to invest (deep tech, being a standout example thus far).

What does this mean for venture moving forward?

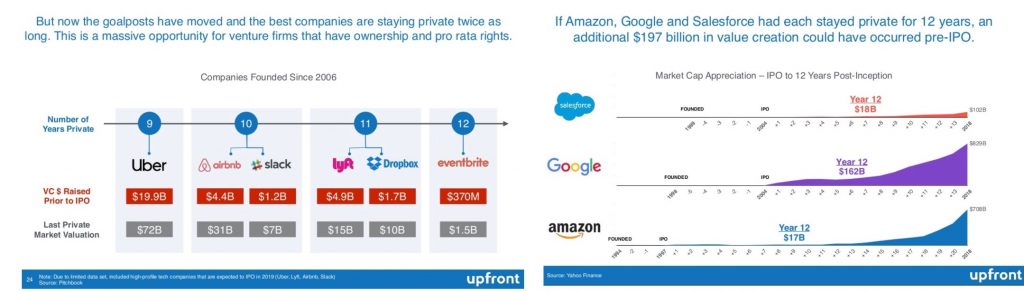

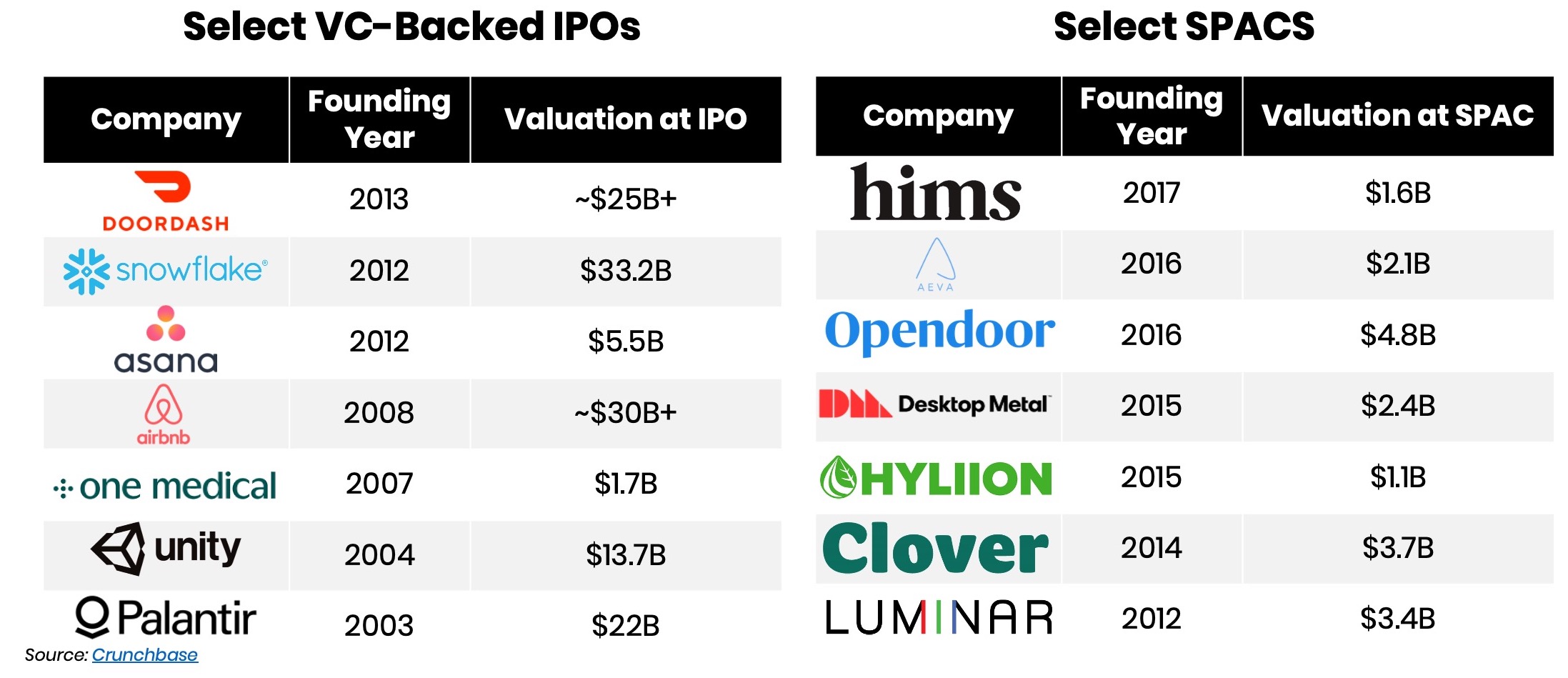

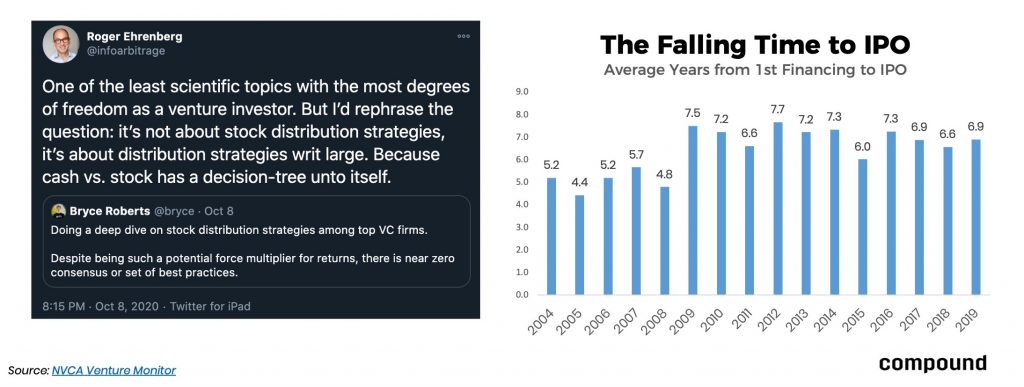

Over the past decade, the strongest narrative surrounding tech was that the private markets will eat returns. The IPOs of yesterday had become the growth rounds of today, with charts like the one above illustrating the private market capture of value for companies staying private for over a decade, versus the prior generation of tech companies going public in <6 years.

I generally still believe this is true, but what the narrative shift around tech, a flying open IPO window, and SPACs have done is possibly bring forth a reversion towards shorter liquidity timelines.

What’s important to understand when we look at these founding years to time to IPO is that while companies in private markets are becoming Unicorns faster than ever before, the mega-unicorns are still taking material time to generate massive, $10B+ value creation relative to their SPAC counter parts which get public 5 years after founding at single digit billion market caps (how much public markets then pump these companies is a different story).

So what VCs must understand is that this less time in private markets could lead to less private market value creation (duh), thus if you believe in the unbounded or poorly understood upside for many companies, we as fund managers must be more thoughtful about our portfolios than ever before.

Startup Pickers to Fund Managers

Early-stage venture capital has always been a bit of a cottage industry within the broader VC asset class. Our jobs as VCs are simplistically split into partnering with founders, and then helping them along the way. Often, seed managers are largely just along for the ride as these companies scale to Series B or C+ stages, hoping to minimize dilution (and deploy dollars) as much as possible before the company exits.

Over the past few years we’ve had a bifurcation of the seed stage market where a massive influx of startup pickers has come along via rolling funds, syndicates, <$15M funds, and even solo capitalists in some regard (though people traditionally think of the higher profile versions of these investors as Series A+ investors with little regard for ownership).

With a shorter time to liquidity and possibly a return to material value creation in public markets, I believe that the early-stage VC fund will be forced to move from company pickers to true fund and asset managers. Being institutional grade and generating alpha no longer just means picking great companies while analyzing position sizing, concentration, ownership, and pro rata dynamics, but also capturing alpha in understanding the upside of these businesses and doing the uncomfortable and terrifying thing: Holding liquid assets that could take your fund from a 3x to a 10x, or the other way around.

Some, like Fred Wilson, will say it’s prudent to take money off of the table along the way. But on the other side there’s a view that is whispered in Silicon Valley which is “don’t believe you’re better than the power law.”

With incredibly deep secondary markets (and more depth coming soon) at the growth stage and faster times to liquidity on the public market side (but possibly smaller initial outcomes), early-stage investors are going to have more opportunities than ever to take their liquidity and run, but possibly at their own peril.

This leads me to believe that LPs will now have to believe that a fund manager both can identify where the power law truly asymptotes or is captured, in addition to all of the other need to believes in this very fuzzy and data-poor asset class. All while trusting that their GPs know what they are doing, potentially sitting on material liquid gains without distributing, as they come back for fund re-ups.

So while LPs don’t pay early-stage managers to analyze their public positions like they do later-stage investors (especially full-stack funds), these two roles could have that similarity in this specific skillset, something that I’d argue has never been shared before.

And that’s where the similarities end.

The Great Bifcuration of Venture Capital

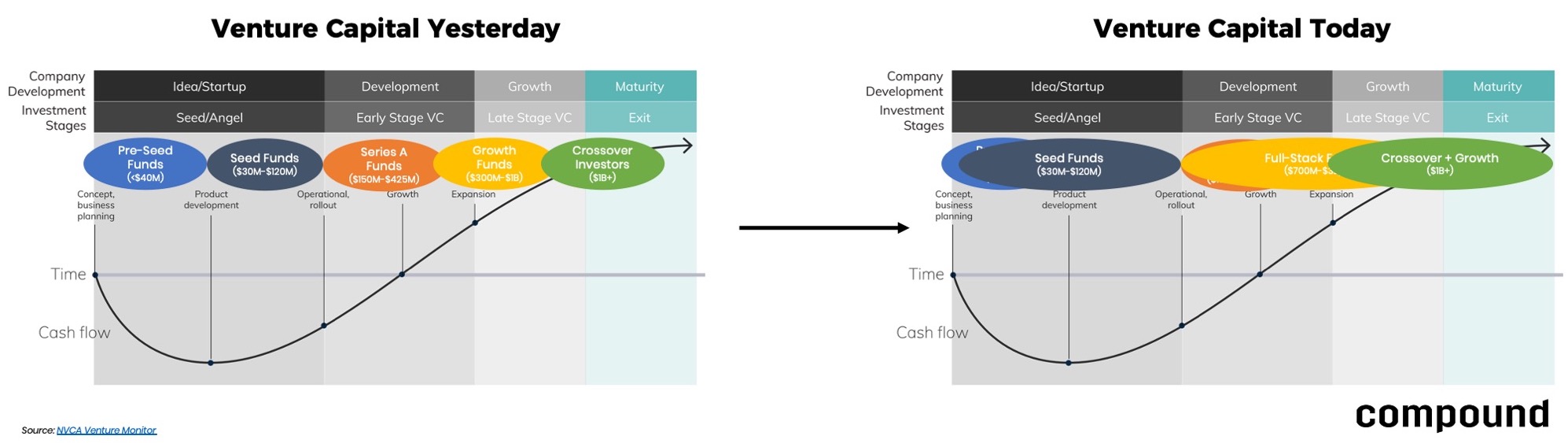

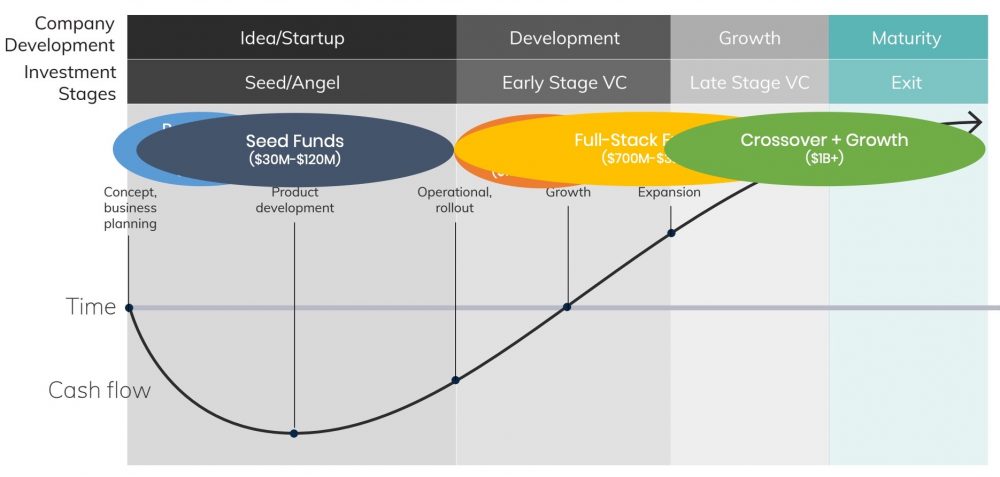

As venture has institutionalized over the past decade+, the chart above got more and more crowded with increasingly specialized products (as happens with maturity). We had pre-seed/seed funds to help founders go from 0 to 1, series A funds to help them scale Product-market fit, growth funds to help build moats, and a newish breed of crossover investors to prepare companies for public markets.

But just like in software, as an industry unbundles, the next wave often necessitates a bundling to land grab the opportunity with economies of scale.

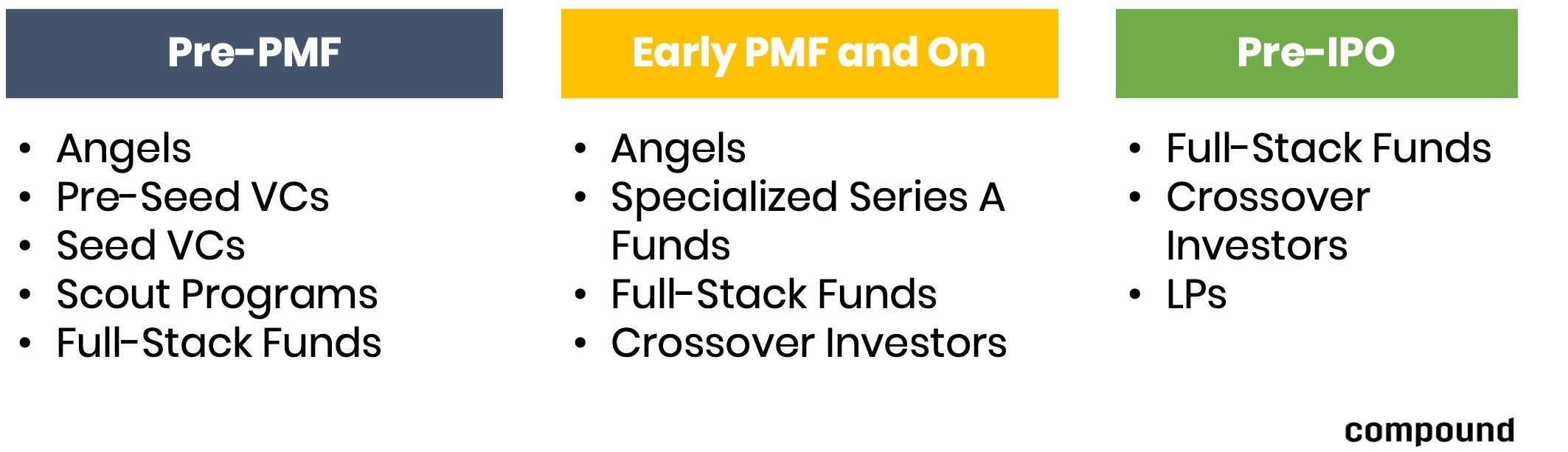

Venture capital is moving to a bifurcation of pre-product market fit and post-PMF investing. What this means is a clear split between firms that specialize in pre-PMF investing (pre-seed/seed VCs, angels, scouts) will all compete across the entire stack. Some full-stack funds will also aggressively go after the seed in order to build stronger competitive positioning for the rounds they really care about (firms like GC have institutionalized this practice).

Once a company shows any semblance of early PMF, the entire ecosystem will compete, funding these companies at 100-300x ARR, and hoping to win pole position to deploy $100M+ into the company over the lifecycle of their growth, and likely hold post-IPO in many regards.

There are a few implications of this moving from early to late:

- Pre-seed funds will compete directly with every other pre-series A investor <$80M in fund size. (footnote: especially as many founders skip pre-seed)

- Series A funds will either have to specialize to win deals on that vector, while pricing at maximum ability, or will be forced to go full-stack. After talking to numerous Series A GPs, I do not believe most Series A firms are going to be able to maintain <$300M fund size and compete over the next few years.

- Solo Capitalists will continue to disrupt pricing models, anchored on the core belief that the market is misunderstanding the TAM of many technology businesses (thus lower ownership is okay), or saying this while building logo capital and social capital to re-bundle in their own right and compete with the full-stack funds in a few years (we’ve seen early public signs of this with certain solo capitalists’ $200M+ funds).

- The idea of Pre-IPO investing will be reserved only for a smaller subset of companies that view material value staying private and look to raise from asset managers that can write $100M+ checks multiple times and/or will hold their positions through an IPO a few years out. (Epic Games’ recent round was a good example of this)

- LPs that increasingly are aiming to go direct will be at direct competition with their Series A+ funds that they have invested in, and will lose/suffer from massive negative selection bias. Only if they are able to align themselves with Seed funds will they be able to truly generate alpha in directs.

So what’s a seed investor to do?

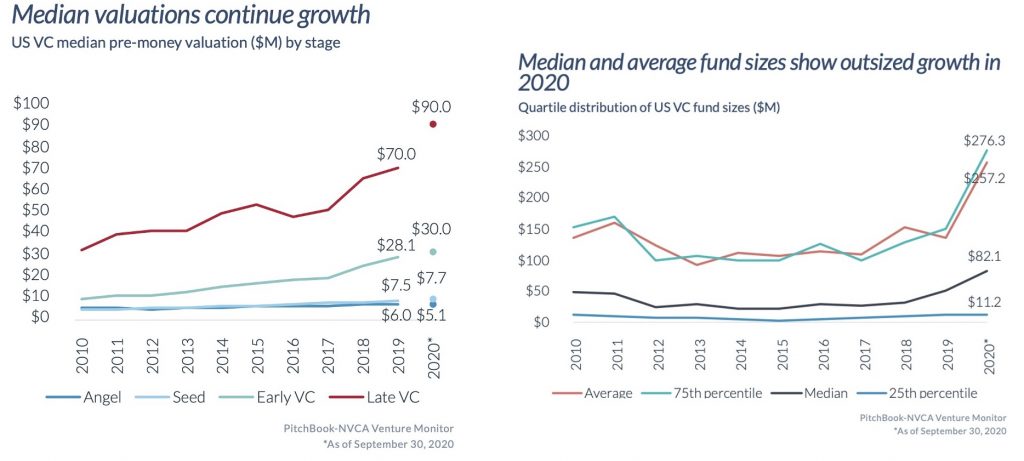

There are a lot of troubling data points for smaller seed funds that people like to point to and talk about. Specifically, rising valuations, increased competition, and larger rounds. While this is true, there is good news.

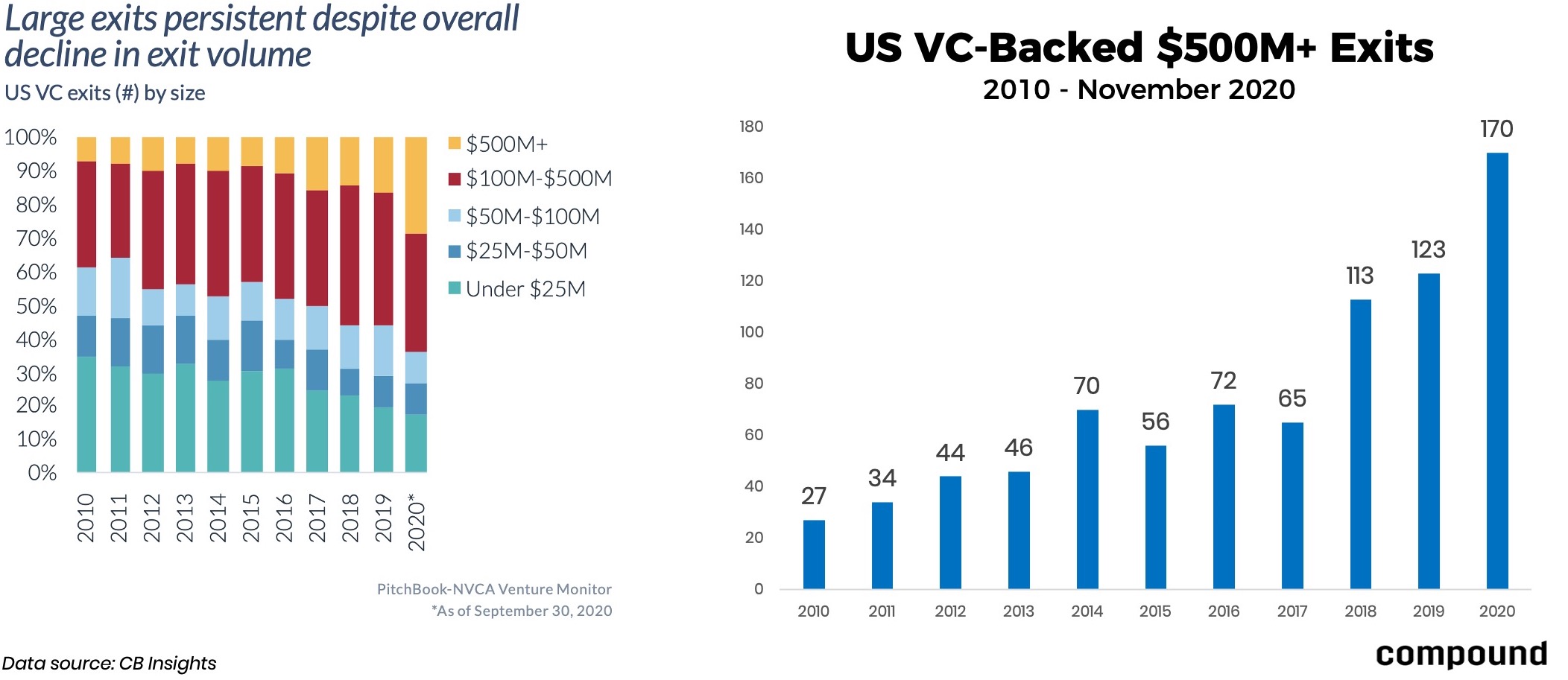

There has been a doubling of $500M+ exits over the past 3 years versus the three years prior (406 2018-Nov 2020 vs. 193 2015-2017). For smaller seed funds, if properly managed, that means that the number of opportunities to return your fund has doubled, and with a stable of unicorns in waiting, I believe this trend will only increase.

But valuations have gone up so you need bigger outcomes, you say?

Yes, but valuations at the seed stages haven’t materially increased relative to what we’ve seen at the growth stages, thus while opportunity set has expanded 2x, the median post-money valuations have probably expanded likely ~25% if I were to qualitatively look at things (or just ~2-3% if you want to look at median pre-moneys per NVCA).

So what does the next few years of venture capital look like? I believe it will be defined by a propensity for an increase of specialized skillsets and a dissipation of pure networks, but I’ve been beating that drum for awhile, so I’ll just summarize it as this:

- The world has recognized the power, influence, and upside of technology companies on the world and the value they can create.

- This recognition has led to material capital inflows towards technology investors and realized value creation in private and public markets.

- Investors must be more cognizant than ever about the bets they are making surrounding upside and fund management.

- Venture Capital as an asset class is quickly bundling and bifurcating. If you don’t figure out which side of the company journey you are firmly entrenched in, and the scope of the product you are offering, you are dead.

Thank you to Max Bulger for early feedback on this post.

Recent Comments